1964 XP-819

Now that Chevrolet has all but formally introduced the world to its first-ever mid-engine Corvette, we felt it was time to share a little of the rich automotive history behind the next-generation C8.

It’s a story that goes back almost to the start of the Corvette program. While some critics are quick to dismiss the latest Corvette as a “European sell-0ut” or a “Ferrari wannabe,” the truth is that Chevrolet has been exploring a mid-engine variant of their beloved sports car for more than half a century.

To more fully appreciate the accomplishment that Chevrolet has achieved with its newest Corvette model, we must look back on the history of the mid-engine Corvette program – a history that takes us back to the sixties and the XP-819 Rear Engine Corvette Prototype.

The XP-819 was developed in the mid-1960’s as an engineering exercise to determine if a rear-engine platform was right for the Corvette program. During that time, Chevrolet was still under a racing ban that had been instituted by the Automotive Manufacturers Association in 1957. The ban had been a major setback for the Corvette program, most especially for Zora Arkus-Duntov and GM design chief Bill Mitchell. The pair knew that the Corette brand needed a strong performance pedigree to survive, especially given many of its early shortcomings in the mid-to-late 1950’s.

While the AMA ban had officially shut down the development of race-ready vehicles by General Motors, two groups within Chevrolet were “secretly” tasked with keeping the division’s performance vehicle program alive. Duntov would lead the continued development of the Corvette program with Chevy engineer Frank Winchell, who’d previously worked on the rear-engine Chevrolet Corvair, would manage Chevrolet’s overall R&D division. Both men wanted to develop a mid-engine, rear-drive street car, and to that end, each began development of experimental prototypes that would feature a rear mounted engine/transmission configuration. Interestingly, the XP-819 ultimately came into being as the result of a a disagreement between Duntov and Winchell.

The argument was actually pretty simple – could a rear-engine sports car with a V8 engine remain competitive during the rigors of a Motorsports event? Porsche had already proven that the layout of such a design was possible, but they’d only ever used flat-four cylinder engines which were both smaller and lighter than the larger V8 models.

Duntov’s team had already completed work on the CERV (Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle) I & II and had tested both extensively. These cars were (and are) considered some of the earliest precursors to a mid-engine Corvette, though their specific purpose was to demonstrate the potential of a rear-mounted engine in any vehicle, not just a Corvette. Utilizing some of the work accomplished by Duntov and his team, Chevy’s R&D department helped develop Jim Hall’s incredible mid-engine Chaparral 2 race car.

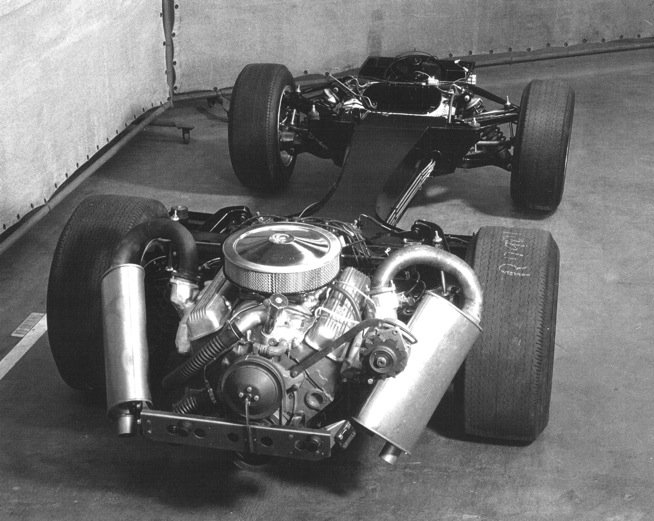

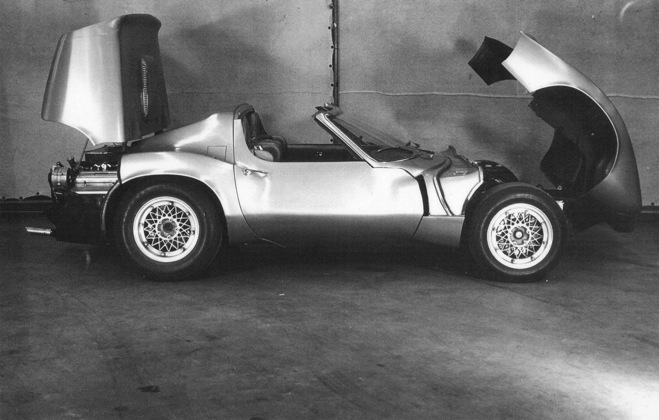

At this same time, Winchell’s team had begun early development of an unusual prototype that they’d dubbed “XP-819”. The car featured a backbone chassis with fixed bucket seats and and engine boled to the frame behind the reaer wheels. Winchell insisted that a balanced rear-engine sports car was possible with the use of an aluminum V8 engine and larger tires, the latter of which would be introduced to help compensate for the increased rear weight distribution.

When confronted with Winchell’s initial concept design, Duntov’s response was that “the car was preposterous.”

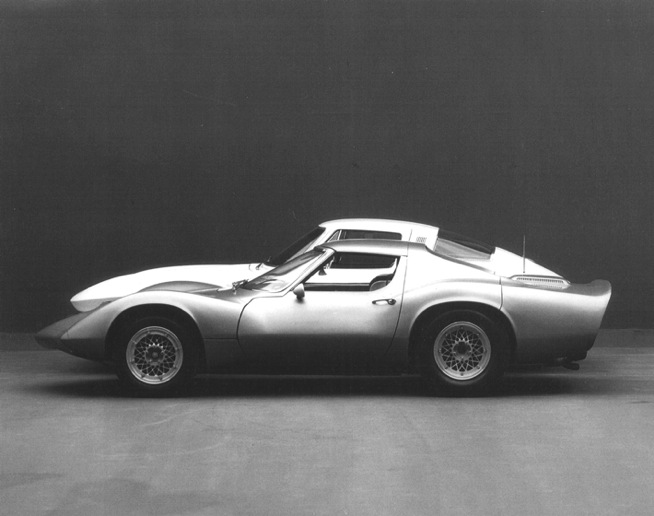

Duntov’s comment didn’t sway Winchell. A more evolved, though still basic automotive drawing was developed based on Winchell’s input that showcased a more fully realized vision of the mid-engine design. The conceptual design was shared with Corvette enthusiasts of that era to garner support. Despite receiving only lukewarm comments from outsiders, Winchell pressed on. He hired Larry Shinoda (an engineer who would later go on to help design the iconic seventh-generation Stingray Corvette) and convinced him to transform his ideas into a viable design that was more aesthetically pleasing and consistent with the design elements in the current Corvettes.

Shinoda set to work on his mid-engine Corvette design almost immediately. He started with the body design from an earlier Corvair Monza GT body design he’d developed. Given all the negative press he’d received prior to this point, Winchell actually asked Shinoda if “he could make something beautiful with the layout (of the new car),” to which Shinoda replied that “a tape drawing would be available after lunch.”

Shinoda and designer John Schinella sketched out the basic design that was ultimately used to create the prototype body. Upon viewing the early artwork and, later, the nearly completed design, Duntov allegedly asked Shinoda, “Where did you cheat?” Duntov could scarcely believe that Shinoda had been able to work the rear engine design into a configuration that still maintained the aesthetic components of a Corvette. Upon further review by Duntov, a working prototype was ordered.

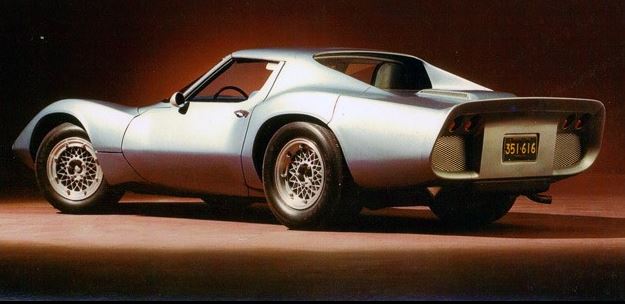

For the next two months, Shinoda supervised the additional styling elements and over saw the fabrication of the first rear-engine Corvette prototype. At the end of those two months, the 1964 XP-819 was completed and ready for testing at the track. The car’s body was filled with advanced features for its time including a removable roof, body-colored urethane bumpers, side door beams and adjustable pedals. Because the engine was bolted into the car’s frame backwards, a reverse-rotation marine V-8 engine was installed. A modified Pontiac Tempest two-speed automatic transmission and transaxle was installed to transfer engine power to the rear wheels.

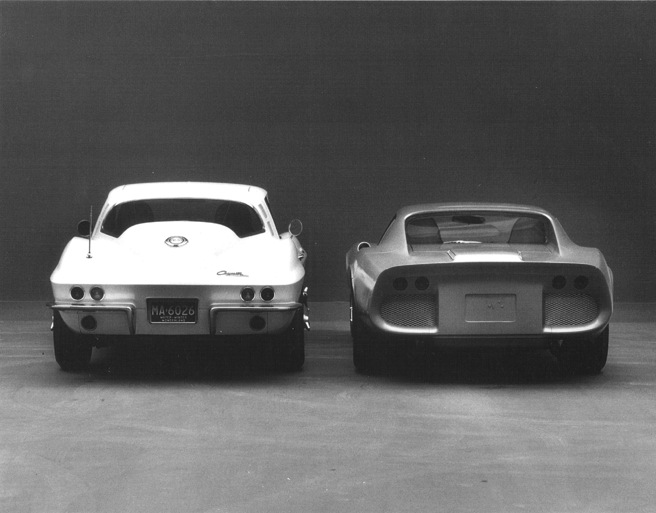

The car was definitely a Corvette despite having a much larger back end than any Corvette that had come before it. Despite the necessary concessions made to the design to house the rear-mounted V8 engine, Shinoda’s design was well received. The design took obvious cues from Bill Mitchell’s Mako Shark Corvette concept along the Chaparral race cars from that era. In fact, the wheels mounted on the XP-819 were the same as those found on the Chaparral racers.

It turned out that Winchell’s theory about a rear-engine V-8 sports car didn’t work out as well as he’d hoped. With all of the added weight – 69 percent of the car’s 2,700 pound curb weight – mounted behind the rear axle, the rear weight bias caused the car to handle erratically. Rapid changes in the driver input would make the car undrivable when pushed to its limit. It wasn’t long before the XP-819 crashed during a high-speed lane change test. Automotive engineer (and future automotive journalist) Pan van Valkenberg had piloted the car during that test run, and some criticized the car’s setup as the cause of the crash. Valkenberg had elected to mount the same (standard) size Corvette rims on both the front and rear axles. Many speculated that the car’s imbalanced weight combined with the lack of larger rubber on the rear axles caused the car to lose control as it made its way down the track. The car bounced off the track walls a couple of times during its run and was significantly damaged to the point of being considered “totaled.”

After its failure at the test track and because of the significant damage it received when hitting the wall, the XP-819 was slated for demolition. However, Chevy division chief Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen, who had been an advocate of the XP-819 program during its development phase, quietly ordered that the remains of the car be shipped to Smokey Yunick in Daytona Beach, Florida. Yunick, an established race car driver of that era, was in the process of building a rear-engine Indy car. Knudsen had informed Yunick to “use any of the XP-819 parts he needed and destroy the rest.” Yunick cut the chassis into three pieces and then adapted the front and rear sections into his race car. However, the development project proved a failure, so Yunick ultimately dismantled the car and placed the XP-819 parts into his paint booth.

In 1977, Yunick hosted a “30 years of parts” sale wherein he sold off a considerable amount of old automotive inventory that he’d accumulated during his years as a race driver. The remnants of the XP-819 were among the old race hardware that he sold during that event. The XP-819 remains were then purchased by Corvette enthusiast Steve Tate. Tate returned the pieces to Missouri and entrusted drag racer Delmar Hines to reassemble the car. Its first public viewing after being restored was at the 1978 Bloomington Gold Corvette show. Twelve years later, Ed McCabe bought the car at a Sotheby’s Estate Auction in West Palm Beach. The car was lent to the National Corvette Museum, where it was displayed for an extended period of time.