It might be difficult to imagine today, but there was a period during one of General Motors’ more challenging financial eras that nearly saw the deliberate discontinuation of the Corvette – the C5 Corvette in particular – long before its eventual arrival in the final years of the twentieth century.

Although it has proudly carried the title of “America’s Sports Car” from its very beginning, the history of the Chevy Corvette is replete with long and challenging intervals of genuine crisis, often resulting in periods throughout the brand’s (more than) seventy-year dynasty that were plagued with significant political, socio-economic, and even legislative landmines that challenged the brand’s long-term commercial viability. When Harley Earl introduced the original Corvette as a “sporty” concept car in January 1953, there was no way he could have predicted the volatile, often uncertain future history his two-seat sports car would encounter throughout its next seven decades of production.

Earl’s original Corvette was hailed by the press as a “masterpiece” at its unveiling in New York City at the 1953 Motorama Show but was soon dismissed by the automotive community at large, garnering the unpopular nickname “the rolling bathtub,” which was not-at-all surprising given that the car had been hastily transformed from a “turnstile queen” to a production vehicle in just six, short months. Despite being a spectacle on the car show circuit, the production car that consumers received was underpowered (equipped with a stock GM “Stovebolt” inline six-cylinder engine), handled poorly, and was slapped together using a variety of existing “parts bin” components to help manage production cost. Within three years of its introduction, GM executives were prepared to cut its funding and halt production entirely. Fortunately, Harley Earl (with considerable direction and support from Zora Arkus-Duntov and Ed Cole) recognized the areas where the Corvette was lacking (namely, power and handling) and worked quickly to transform Chevrolet’s struggling two-door coupe into something that would excite consumers: namely, a track-capable sports car that performed as well as it looked.

By the sixties, the Corvette had established a stronger following, especially after the introduction of the second-generation, split-window Corvette Sting Ray in 1963. For the next decade, the Corvette would flourish, moving from a second to a third-generation model under the watchful eye of GM’s (then) current VP of Design, Bill Mitchell, and through the brilliant artistry of Chevrolet staff designer Larry Shinoda. But even as brand popularity continued to increase, the 1973 OPEC oil embargo and the ever-increasing Federal emission regulations being placed on all automobile manufacturers throughout the seventies put a serious strain on the Corvette’s continued development. By the time Corvette chief engineer Dave McLellan replaced Duntov on January 1, 1975, it seemed as though the Corvette was once more doomed to disappear into the annals of history. Although McLellan and Mitchell were ultimately able to convince GM executives to continue production of the Corvette, its engine size and horsepower were dramatically reduced. By the late seventies and early eighties, the third-generation Corvette had become a dated, bloated, underpowered shadow of its former self. Fortunately, despite these deficits, ongoing popular public opinion of the Corvette kept the brand relevant long enough for GM to green-light a fourth-generation model.

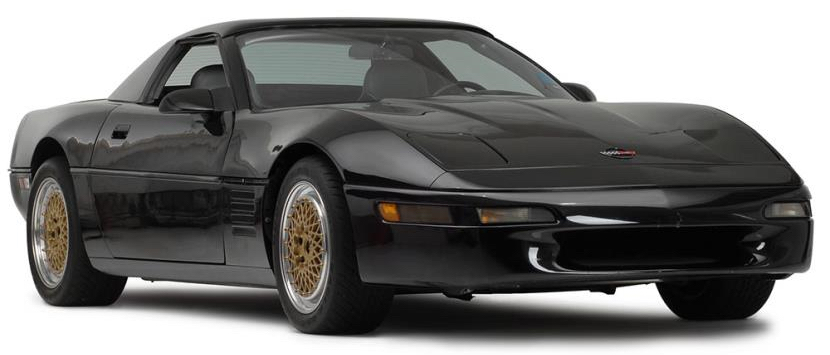

When the fourth-generation Corvette arrived in 1984, consumers and critics alike agreed that GM had successfully transformed the Corvette from a lackluster coupe with outdated styling and technology into a contemporary, high-tech sports car that could, for the first time in the brand’s history, begin to seriously compete with the likes of Porsche and Ferrari. Yes, the early C4 Corvettes were still underpowered (especially by today’s standards), but advances in the car’s aerodynamics, suspension, cornering capabilities, and overall drivability created a level of excitement amongst consumers that had not been seen for a generation. Advancements in fuel injection technology and manufacturing materials helped fortify engine output and, by the late eighties, the Corvette was catapulted to the “King of the Hill” with the introduction of the ZR-1 in 1989 and the GEN II LT-1 engine in 1990 (along with a refresh of the fourth-generation design.)

To the outside world, it would have appeared that America’s Sports Car was headed into a better era than any that had come before….an era of continued and prosperous growth with the seeming certainty the Chevrolet must be nearing the advent of a fifth-generation model.

Little did anyone realize that the polar opposite was quietly taking shape within the hallowed halls and design studios at General Motors.

Changing of the Guard / The Perfect Storm

On November 18, 1992, David Hill replaced Dave McLellan as Corvette’s chief engineer. Like McLellan before him, Hill recognized that the Corvette had established a reputation as a high-performance automobile. He recognized that its continued commercial success would be dependent upon his ability to advance the brand’s capabilities both on and off the racetrack. He had also recognized, as did many in GM, that at the time of his appointment as Corvette’s new Chief Engineer, the Corvette had already entered into a period of economic uncertainty, as evidenced by the steady decline in year-over-year sales numbers. Where sales of the 1984 Corvette had totaled 51,547 units, the 1992 model had resulted in just 20,479 units being sold. To add insult to injury, General Motors was nearing the brink of bankruptcy.

It was for these reasons that GM’s executives decided to cancel the formal development of a fifth-generation Corvette so that they could free up money for the development of other, higher-volume, more commercially viable vehicles.

Despite the growing uncertainty about the Corvette’s long-term viability, Hill knew that the only way to keep the Corvette alive was to simultaneously prepare a fifth-generation concept that would advance the brand’s driving/handling capabilities to as-yet unrealized levels of performance while simultaneously bolstering interest in the fourth-generation model as they secretly advanced the fifth-generation design.

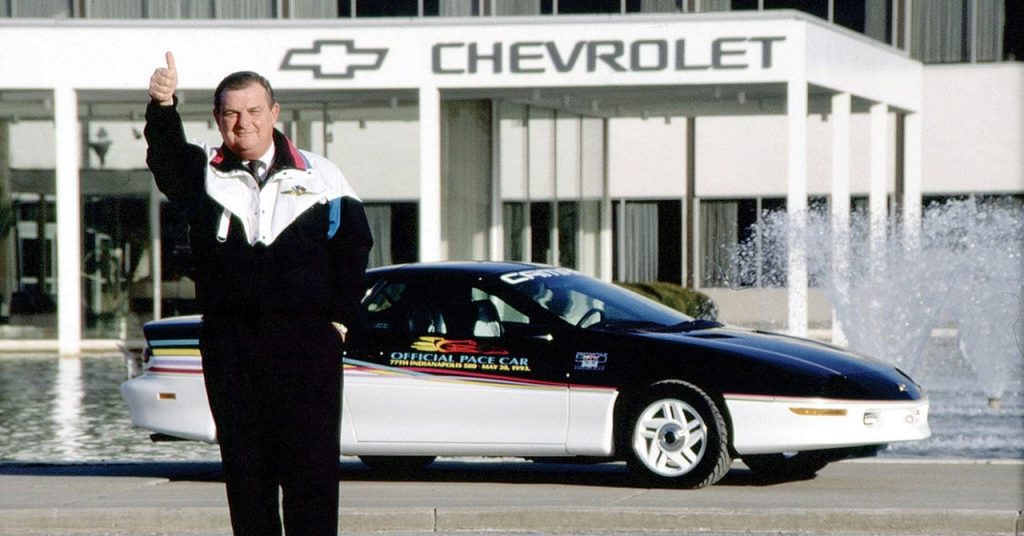

Hill was chiefly responsible for the evolution of several, special-edition C4 Corvettes, each of which was carefully designed to appeal to would-be collectors who had the pockets to purchase each as an addition to his/her private collection. Hill was largely responsible for developing the popular purple-and-white 1995 Indy Pace Car (and its production car replicas.) In 1996, Hill also introduced the Grand Sport and Special Edition models. When equipped with a six-speed manual transmission, each of these cars also came equipped with an LT-4 engine that boasted an impressive 330 horsepower.

Despite all of Hill’s efforts to increase production volume and reinvigorate consumer interest, sales numbers of the C4 improved only marginally over the next four years – 21,590 units in 1993, 23,330 units in 1994, 20,742 units in 1995, and 21,536 units in 1996. It appeared that consumer interest in the Corvette was waning, and many involved wondered if public opinion of the Corvette had waned given the steadily rising pricepoint of the Corvette compared to the advances that had been made in the fourth generation since its introduction in 1984. More than a few automotive publications went so far as to publish comments akin to the idea that the Corvette had achieved a pinnacle of performance that would be difficult to top – especially at the pricepoint that Corvette consumers were willing to pay for “America’s Sports Car.”

Many of the individuals closest to the Corvette – including many of Chevrolet’s top executives as well as many of its engineers and designers – began to wonder if its decades-long dynasty was coming to an end….

..and that’s really where this story of “surviving uncertainty” begins.

Evolution of the C5 Corvette

Dave McLellan / Transmission Challenges

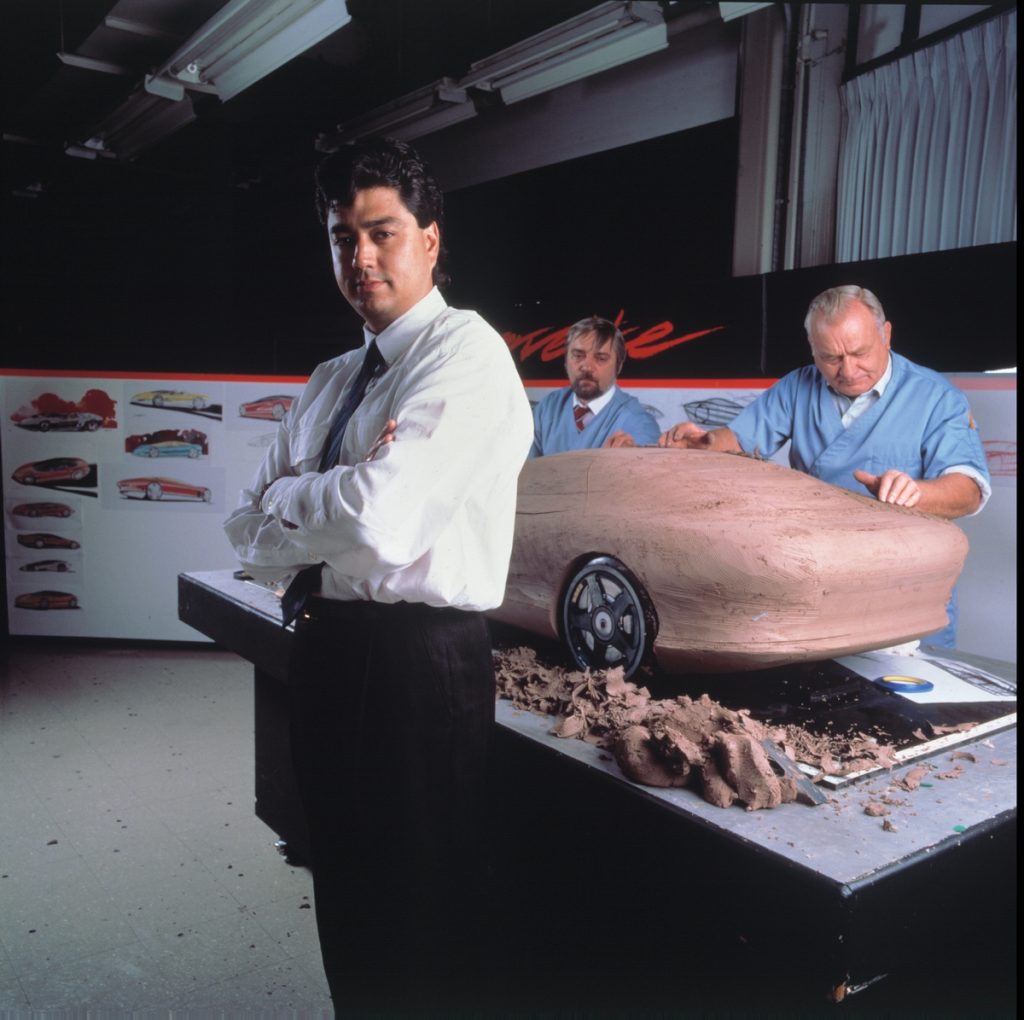

Now to fully understand the complexities of the fifth-generation Corvette’s origin, we need to step back in time to 1989, when Dave McLellan and the design team behind the Corvette, which included such iconic designers as Tom Peters, John Cafaro, and Jerry Palmer, first put pencil to paper and began exploring what a next-generation Corvette might look like and how it would improve upon the fourth-generation model. We also need to understand the political and financial climates of General Motors during this dark period in the company’s history, while drawing attention to some of the other key players in the fifth-generation’s evolution – including Joe Spielman and Jim Perkins – both of whom would provide significant contributions to the Corvette’s continued existence.

For Dave McLellan, the evolution of the C5 Corvette began with a question – how could they (the design and engineering teams behind the current Corvette) top the C4 Corvette? The answer – engineer a completely new car, correcting for issues that had arisen in the development of the fourth-generation model. McLellan felt convicted to engineer the C5 as a convertible to ensure its structural rigidity (in any iteration) from the onset without the need for the massive subframe assemblies that had created such a harsh ride in the C4. This was an issue McLellan had been unable to fully overcome with the C4 when the decision had been made to transform the fourth-generation Corvette from a T-top to a Targa top. Engineering the C5 specifically to be a convertible model first was unprecedented in the history of the Corvette, with the possible exception of the original 1953 model, which had only been envisioned as an open-air coupe during its development.

McLellan asked Lotus Engineering, the division that had been responsible for the evolution of the powerplant in the fourth-generation ZR-1 and which GM had owned a controlling interest in since 1986, to perform an analysis on how a significantly more substantial structural strength could be achieved to enable a new Corvette to be developed as a convertible model. The answer came back almost at once: the next generation Corvette would have to incorporate a torsionally rigid backbone. While the concept was not new to GM, the introduction of a torsionally rigid, centralized backbone in a two-door coupe would require the relocation of the car’s transmission from directly behind the engine to a rear-mounted transaxle.

It is important to remember that, even as early as 1989, Corvette sales volume was on the decline and GM was facing economic uncertainty. While the Corvette already had a manual transmission that could be transformed into a usable transaxle assembly, the Corvette Group and Chevrolet R&D lacked a viable automatic transaxle. When Chevrolet’s R&D engineer speced an automatic for the new Corvette and approached GM’s Hydra-Matic Division to determine what the costs associated with developing a bespoke automatic transaxle would potentially be, the number that came back was staggering: an estimated $80 million in development costs. McLellan knew that there was no way to amortize that much money for a Corvette-only automatic transaxle, but he elected to move forward with the engineering process regardless, confident that GM would eventually provide the necessary funding to make such a transmission a reality.

Interestingly, the solution to the C5’s transmission dilemma was nothing short of serendipitous. Jim Minneker, GM Powertrain Engineer (and 2017 Inductee in the National Corvette Museum’s Hall of Fame), had learned that work had already begun on a new, more rigid Hydra-Matic automatic transmission for GM’s full-size four-wheel-drive-trucks. Minneker inspected the assembly and discovered that the new transmission housing could easily be adapted to a rear transaxle for the new Corvette. And the best part? Since the transmission was being developed for GM’s truck line, one of the top performing divisions of all of GM’s products, the transmission program was already well funded, meaning that Corvette’s R&D budget would not have to cover the $80 million in development costs previously quoted by GM’s Hydramatic Division.

Hydroforming

With the automatic transmission issue resolved, McLellan’s team turned their attention to developing a structurally rigid backbone for the new Corvette. Advancements in technology presented the team with options not available during the development of the C4, but the process of determining the optimal structural solutions would take the combined efforts of Corvette’s engineering team as well as a team of structural analysts.

Corvette body staff engineer Jerry Fenderson advanced the notion of the hydroformed rail assembly. Early on in the structural development of the fifth-generation Corvette’s chassis, it was Fenderson who advanced the notion that the Corvette’s current 2-3-2 frame rail assembly (two rails out front, three rails in the middle section (the third rail adding structural rigidity), two rails in the rear) could be modified so that the outer rails could be made from one long section of steel rather than three, separate sections.

Per Dave McLellan “(it is) a torsionally-stiff backbone…roughly an 8-inch diameter round tube or its rectangular equivalent, which would have to run the length of the passenger compartment. It would then need to connect the entire structure to make the car stiff in torsion. Jerry Fenderson, our Corvette body staff engineer, took the first big step when she saw that the outer rails of the 2-3-2 structure could be combined into one long continuous rail. She committed to taking this on as a separate project.”

To create the exact structural shapes needed to create the C5′s chassis, Fenderson implemented the process of hydroforming. Beginning with a 15-foot (4.572 meter) long, 6-inch (15.24-centimeter) diameter piece of tube steel, each rail was assembled by first bending the tube via conventional tube bending. Once an approximation of the desired shape was achieved, the steel tube was capped at both ends, placed into a die, and injected with water at approximately 10,000 psi. This enormous pressure caused the steel to expand and conform precisely to the shape of the die.

Once each of the two hydroformed side rails were completed, they were tied together using front and rear cross members, and by a centralized backbone tunned which was crafted from sheet steel and welded to the rails behind the engine and ahead of the transaxle. Similarly, the front and rear suspension components – including the upper and lower control arms at all four corners of the car – were constructed from forged aluminum. The upper assemblies were then mounted to the main chassis assembly while the lowers were mounted to large, cast-aluminum cradles. These cradles (two total) were bolted to the front and rear of the chassis assembly – the front to cradle the engine, and the rear to cradle the transaxle assembly.

Testing of this new chassis assembly via advanced computer analysis late in 1992 confirmed what McLellan, Jim Minniker, Jerry Fenderson, and countless others had believed throughout the engineering process – namely that they had created a structurally rigid chassis that would also enable the new Corvette’s body to be packaged around the chassis without the many structural obstacles that adversely impacted the C4 a generation earlier.

Dave McLellan formally retired from General Motors on August 31, 1992, though he agreed to stay on with the company until the end of the year. On November 18, 1992, Dave Hill replaced McLellan as Corvette’s chief engineer….and, in so doing, unknowingly stepped into a quagmire of economic uncertainty surrounding Chevrolet’s beloved sports car.

Uncertain Times

It was around the same time as McLellan’s retirement and Hill’s appointment as Corvette’s newest chief engineer that GM unceremoniously decided to discontinue the development of the fifth-generation Corvette. When McLellan and his engineering team began working on the C5 chassis program in 1989, it was with the belief that the next-generation Corvette would be unveiled as a 1993 model-year product. However, the ever-increasing financial constraints being experienced by GM throughout the late eighties and into the early nineties, combined with the increasingly lackluster sales performance of the Corvette brand, caused many executives to “inevitably postpone” the new Corvette’s production, even though many hated to see their flagship sports car come to an end.

It was also around this time that Joe Spielman and Jim Perkins intervened and (both literally and figuratively) “swept in to save the day.”

Spielman, who was a decades-long Corvette enthusiast and collector, as well as GM’s mid-size-car manufacturing division chief at that time, was the first to voice his objections about the rumored cancellation of the Corvette program. Although GM’s executives had yet to formally announce the termination of the Corvette program to the rest of the organization, rumors began circulating almost at once. When Spielman heard the rumor, he took immediate action in the only way he could. He approached (then) Chevrolet General Manager (and fellow enthusiast) Jim Perkins.

Per Perkin’s memoirs “In 1992, Joe Spielman, head of manufacturing, came into my office one day with a long face. He said ‘There’s a rumor going around that we’re going to kill the C5 program.'”

Perkins, who shared Spielman’s passion for the Corvette, took action at once. In much the same way that Spielman had brought the rumors of the C5’s cancellation to him, Perkins met with (then) GM President Lloyd Reuss, to verify the claims and (if needed) to voice his vehement objections.

“I met with Lloyd Reuss,” Perkins explained, “and he was unequivocal. ‘We need the capital and engineering resources to do the H-car (GM’s full-size sedan line, which included the 1992-1999 Pontiac Bonneville, Buick LeSabre, and Oldsmobile Eighty Eight)”

Even after voicing his continued objections and vehemently defending the Corvette program, Reuss remained unswayed. GM’s financial situation was just too perilous, and concessions had to be made that would maximize the future profitability of the brand. With the Corvette’s sales numbers on the decline and the enormous cost associated with developing an entirely new Corvette platform, Reuss simply couldn’t afford to expend the money on a product he believed, based on the empirical evidence presented to him over the last several years, had lost favor with consumers.

Perkins and Spielman Intervene

Fortunately, Perkins disagreed with Reuss’s position surrounding the Corvette. More than that, Perkins had enough autonomy as Chevrolet’s GM to do something about it. He had remained engaged with McLellan’s team as they progressed through the development of the new Corvette chassis, and he recognized that the chassis program had reached a point where field testing was paramount to keep the program moving forward. Additionally, he knew that the performance design team needed to begin working on the new car’s exterior and interior designs if Chevrolet had any chance of bringing a fifth-generation Corvette to market within the next five years.

Despite the potentially devastating/career-ending impact the decision could have for both of them, Perkins and Spielman pulled money from their respective operating budgets to continue the work being done by the Corvette design team.

“Jim came up with a million dollars out of his advertising budget,” says Spielman (from a 2018 interview in Car and Driver magazine), “and I looked across the rest of my organization and found half a million here, a hundred thousand there, and put enough together to build a working mule with a new structure under the old car.”

In total, Perkins and Spielman clandestinely pulled together a total of $2.5 million from their respective budgets, with a significant portion of that money coming directly out of Perkin’s marketing budget. The infusion of new funds was enough to keep the C5 program alive, at least in the short term, but the long-term viability of the C5’s design/development program required some quick work on the part of Hill and his team.

“We desperately needed to build a vehicle,” Hill explained, “and we needed it in time for the North American Strategy Board (NASB) Concept Approval meeting, (which was) just 90 days away.”

The NASB is a group within General Motors that focuses on developing and overseeing the company’s strategic direction for the North American market. This group focuses on decisions around vehicle production, sales, marketing, and overall market positioning within the United States and Canada. If Perkins had any chance of keeping the C5 program alive, he needed something tangible to present to the NASB that could/would promote a favorable outcome.

Utilizing a shop outside of GM, Hill and his team assembled a mule car that incorporated McLellan’s all-new hydroformed backbone structure and rear transaxle with a “ragged”1992 model year, fourth-generation Corvette body. The car became commonly known as the CERV IV-A (Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle IV-A) and was driven extensively to test the newly hydroformed chassis on various road/driving conditions without drawing outsider attention to GM’s new Corvette development initiatives.

Says Perkins, “We were driving it at the Mesa, Arizona, Desert Proving Ground and everybody was blown away with what we had. For example, when you ran over ripple strips with the old car, you got a memory shake that would rattle your teeth. But the C5, even with that old C4 body on it, just settled down and—burrrr—ran over it. So we knew we had something.”

Perkins and the NASB

Shortly after experiencing the CERV IV-A / C5 test mule himself, Perkins called for a meeting with Reuss and some of GM’s other top executives so that they could have a frank “nose-to-nose, heart-to-heart” discussion about the Corvette and why General Motors should continue building it. Perkins’s initial meeting with Reuss was based almost entirely on the importance of brand recognition as well as the generations-long emotional sentiment that the Corvette conveyed to both past and present consumers and enthusiasts. Lacking from the conversation was anything even remotely resembling a financial analysis to help justify and decision. He hoped to play to their emotions….and fortunately for the Corvette brand, Perkins knew how to be compelling when he needed to be.

Says Perkins (in a 2014 MotorTrend interview) “We had not yet developed a business case because everything had been done on the QT (in secret), but we didn’t have a choice. We had to do something. I finally got with Lloyd and Mike Mutchler (who ran Chevrolet-Pontiac-Canada) and had a nose-to-nose talk about that car and why we should continue it. Corvette was among the best-known names in the automotive world, I said, and if you don’t have enough confidence in me to trust my judgment that we can make money on this car, then I shouldn’t be here.”

Perkins’s compelling arguments won him a begrudging decision from Reuss for the Corvette team to continue their development efforts, at least until a formal business plan with the proper financial justifications was presented to the NASB. Perkins, feeling a sense of victory at the overturned decision to stay the execution of the C5 development program, thanked his colleagues and prepared to depart, when Reuss stopped him.

“Where did the money come from to take it this far?” he asked of Perkins.

Perkins’s response was short, sweet, and to the point – with enough specificity to answer the question and enough ambiguity to avoid giving a real answer. He told them ” I think I told them we found it. I did confess that we had reallocated some money from other areas in the organization, but I didn’t tell them which ones. I think they really didn’t want to know.”

Now that he had Lloyd Reuss in his corner, Perkins focused on the monumental task of convincing the NASB to keep the C5 program alive and to see it through to fruition. Almost immediately following his meeting with Reuss, he contacted Spielman and Hill and told them that they needed to get as many high-level people and NASB members as possible into the C5 mule car before the Concept Approval meeting with the NASB. While Reuss knew the NASB would base much of their final ruling on the commercial viability of the C5 Corvette, he knew the best way to market to his audience was to show them what was coming.

When the time came for Jim Perkins to present his business case to the NASB, he focused on three specific areas. First, as was required before any other arguments defending the brand would be heard/considered, Perkins established that the efforts to improve the C5 Corvette’s performance and overall quality would translate into greater customer satisfaction and profitability. Per Perkins, “(it was estimated that) the C5 financial projections were 250 percent better than the C4″

While the supporting evidence behind that claim should have been more than sufficient to remove any doubt from the NASB’s decision to continue forward with corporate production of the new Corvette, Perkins also used this opportunity to lecture on the importance of the Corvette stating “the Corvette was the purest example of what GM and America could be proud of – an American icon that they had no right to cancel.” Before presenting to the NASB, Perkins had also tasked his team with tallying up the total number of magazine covers the Corvette had appeared on since 1953 – more than 800 in total. That statistic, when combined with the estimated profitability of the C5 Corvette and Perkin’s compelling arguments, ultimately led to the formal executive approval of the program by GM CEO Jack Smith and the NASB in 1994.

Styling the C5 Corvette / The Stingray III

Around the same time that Bob Perkins began his campaign to save the Corvette, GM design leader Chuck Jordan launched an internal design competition with GM’s design studios to create an original design proposal for the fifth-generation Corvette. As part of this competition, Jordan reached out to John Schinella, then director of Chevrolet’s Advanced Concept Center in Los Angeles, and challenged him with developing the “Califonia Corvette” – a smaller, lighter sports coupe than the outgoing C4 model. Jordan wanted this new Corvette concept to be akin to the types of sports cars that had begun gaining popularity with consumers on the West Coast.

Schinella made some determinations on how the chassis and drivetrain should be configured based largely on the engineering work previously performed by McLellan’s engineering group in Detroit. Using McLellans work as his baseline, he began defining the look of the car through a series of quickly rendered sketches. Once he had settled on a satisfactory design, he distributed the sketches to his team at the Advanced Concept Center with the instruction that they should critique the designs and offer suggestions for improvement. The sketches he received back a few days later provided the foundation for one of the C5‘s key conceptual designs – a car that would become known as the “Stingray III.”

The Stingray III incorporated design elements from many of the early Corvettes, including motifs from earlier concept models. Schinella understood that the success of any future Corvette would need to incorporate recognizable styling elements from earlier generations while simultaneously offering consumers something exciting and new. The Stingray III included both. It featured a stretched wheelbase and wider proportions, a bobbed tail, and a steeply raked windshield.

While the car was aesthetically exciting and came loaded with all sorts of cutting-edge technology, the car lacked a key component synonymous with Corvette – a V8 engine. Instead, Schinella had equipped the Stingray III with a high-output V6. While initial public opinion of the Stingray III was favorable when it appeared at the 1992 Detroit International Auto Show, consumer opinion declined quickly when it was discovered that this new Corvette concept would come equipped with anything less powerful than the current LT1 V8 platform found in even the base model C4 coupes and convertibles.

Tom Peters and John Cafaro

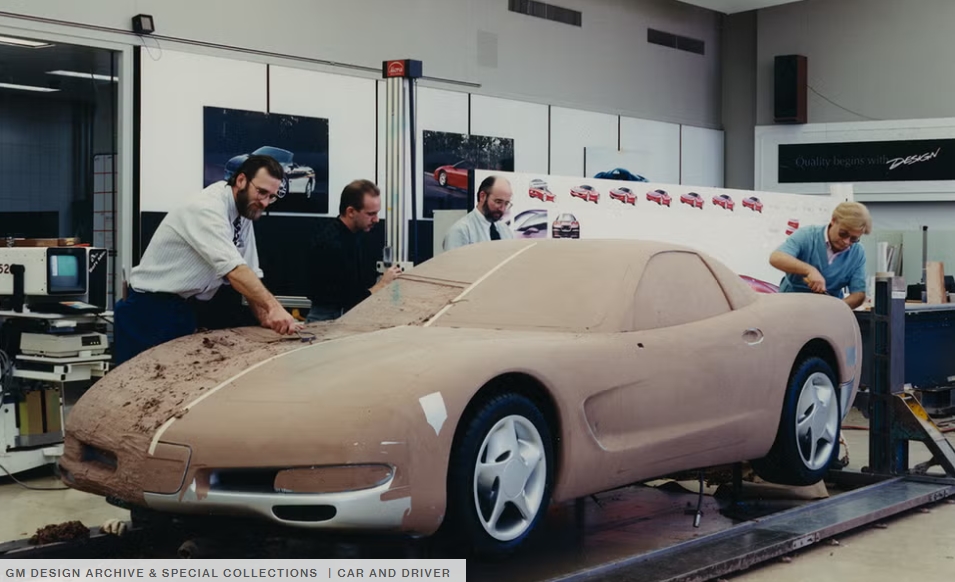

In addition to the Stingray III, Chuck Jordan’s design competition resulted in more than sixty scale models of prospective, fifth-generation Corvette models. Several of these models were collected from various studios across the United States and were then transported and displayed on the patio of the Design Center in Detroit, Michigan. Once assembled, the showcase of models was opened to both the Design Center staff and executives, all of whom were encouraged to critique the designs and provide feedback on which of the models were their personal favorites. It was through this process that the models were narrowed down until two finalists were selected as prospects for continued development.

The first of these was a design created by Tom Peters. Peter’s styling buck bore a fairly strong resemblance to Schinella’s Stingray III, though it incorporated practical design elements that also made it viable as a would-be production prototype. Like Peter’s Corvette Indy and CERV III concept cars before it, this model was sleek and beautiful, exuding a sophistication and elegance that was fresh and new, yet unmistakably Corvette.

The second of the designs selected was a model created by John Cafaro, then head of the Corvette Production Studio. Like Peters’s model, Cafaro’s concept was sleek and beautiful, though his design drew more directly drew its inspiration from several race cars that he’d helped design during his career at GM. Cafaro’s model was optimized so that it could be adapted for use as a race car while still establishing a design motif that expressed the beauty and feasibility of a roadworthy production sports car befitting the Corvette name. Cafaro developed his model in the basement of the Design Center in a remote area known as GM’s “skunk works.” Working largely in secret, Cafaro refined his design to a point where it was ready to be rendered as first a clay, and later, a fiberglass appearance model that he called simply “Black Car.”

In Richard Prince’s Book ” Corvette: 70 Years / The One and Only,” Cafaro recounted his experience developing Black Car. “Black Car was a very pure statement, inspired by various race cars more than anything else, and a lot of credit goes to David Snabes, a GM Designer sculptor who modeled both the scale and full-size clays of the car, and beautifully brought to life what I was trying to express.”

Many of GM’s executives and design studio staff thought that Black Car was a strong, stunning design that could/should be developed as the fifth-generation Corvette. Unfortunately, several obstacles delayed Cafaro’s design from evolving beyond its full-scale fiberglass model stage. First, GM’s prolonged day approving production of a fifth-generation Corvette, as previously outlined above, interrupted the workflow and left many within the design studios questioning whether there’d even be a fifth-generation Corvette. However, this was less impactful than the newly implemented market research studies and consumer clinics, both of which were firsts in the history of designing/developing a new Corvette model. Cafaro’s model lost some of its popularity within the design studios because of varying consumer opinions about Black Car. What’s worse, GM executives looked to Cafaro (and others within the design studios) to integrate the consumer feedback they were receiving into future Corvette designs.

Per Cafaro “Black Car was very refined, and there was a certain purity to its beauty, but when you came up to the car and looked at it closer, it was really a brutal design. In the (consumer) clinics, most people didn’t understand it.”

Despite these setbacks, along with more stringent engineering standards than any Corvette before it, Cafaro’s Black Car would win out and provide Cafaro with the foundational design he needed to create the C5 Corvette’s final design (once the project had been greenlighted by GM.) Cafaro’s final design was the product of a team of designers from the Corvette Production Studio, including Mark Kaski, Dan Magda, and Randy Wittine. As the design for the C5 evolved, it was celebrated as being “beautiful,” “forward-looking” and “thoroughly contemporary.” When comparing the final production car to Black Car, there’s no denying that many of Cafaro’s signature design motifs had been retained through every iteration/refinement of the design. At the same time, Cafaro recognized the importance of integrating some of the iconic design features synonymous with the Corvette, so the car was equipped with oval taillamps, bodyside coves/vents (similar to those found on every Corvette since 1956,) and of course, the iconic tuckaway headlamps (which first made an appearance in 1963, and which would remain a staple of Corvette until the end of the fifth-generation model in 2004.)

A Fusion of Design and Engineering

One of the more interesting aspects of the C5’s evolution was that the latest iteration of the Corvette would be the catalyst of Chevrolet’s return to factory-backed racing. Cafaro’s “Black Car” design offered far more than just a beautiful aesthetic. Instead, it was developed utilizing Cafaro’s knowledge and history of building race cars. Hill, Cafaro, and the team behind the new Corvette envisioned the C5 as a means for Chevrolet to return to the global racing stage, and to build a world-class sports car that could compete with the best German and Italian sports cars on the market – both on and off the racetrack. Where earlier iterations of the Corvette had always been generally accepted as a “well respected” but also “generally underpowered American sports car,” the C5 was the first Corvette to embrace the “form follows function” mantra, an engineering edict that would become the cornerstone of every Corvette that came after it.

The team at Corvette, along with many of the executive leadership at Chevrolet, recognized that the Corvette could achieve greater success by appealing to a global audience. They also knew that its success outside the United States would require its dominance on the world racing stage. In a very real way, it was recognized that the fifth-generation Corvette would be paramount in rebuilding Chevrolet’s brand – but to do so, it had to earn its place amongst the great sports cars found around the world while still being affordable in the marketspace it had always occupied to ensure its commercial viability and long-term sustainability.

As Cafaro’s exterior concepts evolved towards a production vehicle, the engineering group behind Corvette subjected his designs to extensive wind tunnel testing to create an extremely aerodynamic sports car profile. Every aspect of the car’s exterior, from the car’s mirrors, door handle recesses, front and rear fascias, and overall bodyline, were scrutinized and refined to a point that the car achieved an industry-leading 0.293 coefficient of drag, the lowest Cd of any production automobile being manufactured at the time of the C5’s development and initial production. To achieve this, almost every component (and most mechanical assemblies) introduced on the C5 was brand new and uniquely developed for the newest Corvette. Each of the body panels was constructed of SMC (Sheet Molded Composite), which was a lightweight composite material made of fiberglass bonded and blended with plastics. In addition to creating incredibly smooth body surfaces, SMC also afforded the C5 Corvette significantly higher mitigation from damage due to contact bows thanks to the rigidity of the updated material. While Chevrolet had previously halted development of the fifth-generation Corvette because of severe financial concerns/constraints, the investment in creating such an aggressive design profile, and the development of new, higher-grade body panels was not an act of retaliation on the part of its designers, but rather a continuation of the mantra that “form followed function” and, as such, this convention was needed for what was to come next….you see, Corvette was getting ready to go racing!

“The most satisfying part of (the) C5 was its aero balance and performance,” explained Cafaro. “When the car was introduced, people didn’t know we were going racing with the C5, but that was a big factor in the design and seeing the car perform on track with great success, and knowing that we got it right, that’s the most satisfying part to me.” (from “Corvette: 70 Years / The One and Only,” by Richard Prince).

Although we will cover the subject of Corvette’s return to racing in greater detail in another article, there are a couple of key items worth noting here.

First, Corvette Racing was initiated by none other than Zora Arkus-Duntov in the late 1950s. Duntov’s conviction that the Corvette would achieve greater commercial success if it could compete in racing became the catalyst behind the brand evolution, even after the AMA (Automobile Manufacturers Association) banned factory-supported racing following the 1955 Le Mans disaster and the 1957 NASCAR Mercury Meteor grandstands crash. It took nearly forty years for GM to return to racing with the creation of the Corvette Racing program. Initiated by Herb Fischel in 1996, the Corvette Racing program was established as a cooperative with Pratt & Miller Engineering, who were chiefly responsible for the creation of the C5-R race car (in cooperation with GM), and Doug Fehan, who would helm the racing team from its inception.

Second, it was Doug Fehan who approached Gary Pratt and Jim Miller and informed the pair that Chevrolet intended to race the fifth-generation Corvette on the world stage. It has been reported that Fehan approached Gary Pratt and made the statement “We (GM) want to race this car (the Corvette.) You tell us where it will be competitive, you test it, and you prove to us – in private -that it can win. Do all that and we will make funds available to campaign it over multiple years.” While nobody could have imagined the long-term success that the Corvette Racing program – a venture/cooperative between GM and Pratt & Miller Engineering – would go on to achieve over the next 25+ years, beginning in 1999 with the introduction of the C5-R at that year’s Rolex 24 Hours of Daytona as part of the American Le Mans Series.

Thirdly, it is worth noting that the C5-R race car test mule started its existence as a regular, production 1997 C5 Corvette coupe. That car would go on to complete more than 4,000 miles of rigorous testing at the hands of such legendary drivers as Ron Fellows and Chris Kneifel. It was that test mule that would lead to the development of the C5R-001 by Pratt & Miller Engineering. Talk about “form follows function?” That’s the good stuff right there…

An Affordable Interior

Even after the decisions had been made to greenlight the production of the C5 Corvette and to create a racing program based around the new Corvette platform, cost consideration was still a significant factor that the Corvette engineering and design teams continued to battle throughout the car’s evolution. As with almost every aspect of the car, there were continued delays in the car’s interior development due in large part to the continued financial troubles that GM endured throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s. Even so, interior engineer Jon Albert and his team were committed to creating an interior that improved upon every Corvette that had come before it. They wanted an interior that provided greater comfort, improved fitment, fewer “squeaks, and rattles”, and offered consumers “more sophisticated materials” than those that had been incorporated into the interior of the outgoing C4 Corvette. At the same time, they needed to ensure that the new interior of the Corvette still provided consumers with an undeniable association with earlier iterations of America’s Sports Car.

Thanks to the work performed by McLellan and his engineering group early on in the C5’s development, Corvette’s new chassis had eliminated the tall door sills that had provided structural rigidity in the fourth-generation model, but which also created a physical barrier when entering and exiting the car. Utilizing the hydroformed, central-backbone assembly revolutionized by Jerry Fenderson, Albert’s team was able to provide consumers with a more spacious interior that included approximately 1.5 inches (3.81 centimeters) of additional headroom and 3.4 inches (8.64 centimeters) of additional hip room. Additionally, the relocation of the transmission to the rear of the car eliminated the large transmission tunnel found in earlier iterations of the Corvette, most notably in the C4 model. This advancement, along with the C5’s longer wheelbase, afforded both of the car’s occupants with longer, more spacious footwells. To date, most Corvette enthusiasts agree that the fifth-generation Corvette has one of the most comfortable, most spacious interiors of any generation, either before or since, (with the possible exception of the new, mid-engine Corvette that was first introduced in 2020.)

In addition to its improved ergonomics, Albert and his team were also successful in producing an interior that improved the overall quality of its predecessor. When compared to current models, the C5’s interior may be seen by some as “cheap” or “plasticy,” but in its day, it was considered to be a significant leap forward in terms of material quality, noise reduction, and overall aesthetic. The cockpit was carefully configured to encapsulate the driver, allowing easy access to all of the car’s many control surfaces. Where the C4 featured a long, flat dashboard surface with controls spanning much of its length, the C5’s dashboard incorporated a wraparound design that made the driver feel like he/she was seated in the cockpit of a fighter jet. Analog gauges replaced the “techy” digital gauge of the fourth-generation model, providing the driver with a speedometer and tachometer, as well as oil pressure, fuel, level, and engine temperature gauges directly in his/her line of sight. Adding to this aesthetic, all of the gauges were lit using blacklights, which provided drivers with brilliant, almost ethereally lit gauges during night driving that were easy to read but equally easy on the eyes, allowing for greater visibility of the road surfaces without the glare of a more conventionally lit dashboard.

The re-introduction of analog gauges in the C5 Corvette was a deliberate throwback to the earlier Corvettes, as was the introduction of a “twin cockpit” motif wherein both the driver and passenger felt that their individual compartments were structured to encapsulate them. The twin-cockpit design included structural arches over both the driver-side instrument panel and the passenger-side dash assembly. Each created the “illusion of a wraparound canopy, once more creating an understated by undeniable aesthetic akin to the wraparound cockpit of a fighter jet. The “fighter jet” aesthetic has since been incorporated into many of the later-model Corvette (both interior and exterior) designs, most especially the C6, which used design cues from the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18 Hornet, and the C7 Stingray, which incorporated several design elements from the U.S. Air Force’s YF-22 Raptor fighter jets.

The Heart of the Beast

The financial (and resulting developmental) delays in the fifth-gen’s evolution unintentionally allowed Chevrolet to introduce its latest, most powerful powerplant to date as the heart of the C5 Corvette upon its arrival in 1997. So it was that the C5 Corvette became the benefactor of Chevrolet’s new Gen III small block, LS1 engine.

At the core of the Gen III LS1 engine was a block constructed from aluminum featuring a deep-skirt, closed deck design, with ultra-thin, cast-in cylinder liners. A “deeper skirt” meant that the new engine would be slightly larger than its predecessors as the engine block extended below the centerline position of the crankshaft within the engine. The deeper skirts also strengthened the block and provided it with improved rigidity. The use of aluminum, meanwhile, allowed for appreciable weight reduction over the outgoing cast-iron small blocks. Point of fact, the 1997 LS1 engine was nearly 100 lbs (45 kg) lighter than the outgoing Gen II LT1 engine found in the 1996 C4 Corvette, with the LS1 block weighing in at just 107 points (48.53 kg) versus the LT engine block, which weight 195 pounds (79.38 kg). Four-bolt main bearing caps were cross-bolted to the LS1 block to maximize its strength and made the engine block far stronger than any of its predecessors to date.

The LS engine also featured a cast-aluminum oil pan and cast-aluminum cylinder heads fitted with roller lifters and roller rockers designed to minimize friction. The head castings featured relatively tall and narrow cathedral-shaped ports that were identical, providing evel flow to all engine cylinders. These unusually shaped ports delivered the desired volume and flow in the space between the head bolts and inline push rods, and allowed for the optimum placement of the fuel injectors. The long runner intake manifolds were constructed of a composite material that was lighter and better flowing than any previous engine and helped to insulate the intake charge. They provided increased airflow into the cylinders at low revolutions, thereby increasing engine torque. Hypereutectic (aluminum allow) pistons replaced the cast pistons, providing greater durability and thermal stability. The camshaft featured a hollow core for reduced mass. Even the oil system was revamped for the new LS1 engine, with the oil pump relocated to the front of the engine and driver from the camshaft, resulting in a reduction of one inch (2.54 centimeters) off the total engine height.

Complimenting the Gen III LS1’s mechanical components was a plethora of updated/improved electronic systems. The conventional distributed ignition system was replaced with individual coil packs for each engine cylinder. These coil packs were operated and synchronized by the engine’s computer. The firing order on the engine was also updated. Whereas earlier Chevrolet small-block V8 engines utilized a 1-8-4-3-6-5-7-2 firing order, the Gen III LS1 firing order was changed to 1-8-7-2-6-5-4-3. This was done to reduce engine vibration and stress on the engine’s bottom end.

Manufactured in Romulus, Michigan, the Gen III LS1 V-8 engine was first introduced in the 1997 Corvette and was officially rated at 345 horsepower (247 kW) at 5,600 rpm and 350 lb-ft (475 Nm) of torque at 4,400 rpm. It propelled the Corvette from 0-60 mph (0-100 kph) in just 4.8 seconds, resulted in a quarter-mile time of 13.2 seconds at 110 mph (177.03 kph), and allowed the C5 Corvette base model to achieve a top speed of 172 mph (276.81 kph). The LS1 engine represented the most innovative, smoothest running, cleanest burning, most durable, reliable, powerful, and fuel-efficient (EPA rated 18 mpg (city)/25 mpg (highway) when equipped with an automatic transmission, and 19 mpg/28 mpg for those equipped with a manual transmission) small-block engine ever produced by Chevrolet up to that point in time. The introduction of the LS1 engine enabled future C5 owners to circumvent paying a”gas guzzler” tax. After additional improvements were made to the Gen III LS1 in 2001, engine output was further increased to 350 horsepower (261 kW) and 365 lb-ft (495 Nm) of torque (375 lb-ft (508 Nm) of torque in Corvettes equipped with a manual transmission.) The LS1 powerplant was so well received by consumers that it remained the only powerplant offered by Chevrolet in all base model Corvettes (coupe and convertible) for the entirety of the fifth generation’s production run (1997-2004.)

The Fifth Generation Corvette Arrives

The fifth-generation Corvette was officially unveiled on January 6, 1997, at the North American International Auto Show in Detroit Michigan, nearly four years later than was originally planned when McLelland had started working on the structural underpinning of a new Corvette in the late eighties. Although the C5 had been intended to replace the outgoing C4 on the Corvette’s 40th Anniversary (in 1993), the added time (a result of GM’s financial struggles and the resulting developmental delays they caused) enabled all involved with the fifth-generation model the extra time (and added pressures to get it right!) that was needed to develop a world-class sports car. Ironically, the 1997 Corvette was only offered as a coupe, even though the car was engineered to be a convertible from the very beginning. This was largely due to ongoing financial constraints within GM. The Corvette program had been given the green light, but monies were still tight and the added R&D was simply out of reach for the C5’s freshman year. Fortunately, the 1998 model year would see the introduction of a convertible model, and said C5 convertibles would be the first Corvettes since 1962 to include a trunk.

When looking at the history of the C5 Corvette, it is worth noting that the car proved to have enormous commercial success as compared to the fourth-generation model….with one possible exception. When the 1997 model debuted, Chevrolet managed to sell a meager 9,752 units in its first year of production.

Given that the 1996 MY resulted in 21,536 total units, and also given that GM considered canceling the fifth-generation model due to a lack of sales volume, how is it that the C5 Corvette survived its inaugural year after selling less than 10,000 units?

The answer can be found in the dates surrounding the 1997 Corvette’s reveal and subsequent production start.

Traditionally, the production of a new model year (MY) car at almost any automobile manufacturer begins sometime in the third or fourth quarter of the previous year. Case in point, Corvette production of a new MY will typically begin in July-September of the previous year. By the time the new year (and corresponding model year) has been officially “rung in” at midnight on New Year’s Day (January 1st,) thousands of automobiles designated as that model year have already been produced and sold to consumers.

This wasn’t the case with the 1997 Corvette. As previously stated, the C5 Corvette was unveiled on January 6, 1997, and didn’t start production until March 7, 1997. Considering that the convertible came on the scene as a 1998 MY Corvette in August 1997, this left GM just five/six months to produce the 1997 MY Corvette. As such, 9,752 units in five months is actually pretty good!

Of course, the story gets better from there. The 1998 model year saw 31,084 units, the 1999 model year (which included the FRC – Fixed Roof Coupe variant of the C5) resulted in 33,270 units, 2000 saw 33,682 units, and 2001, which saw the arrival of the now-legendary C5 Z06 coupe, resulted in 35,767 units! While 2001 would prove to be the C5’s most successful production year (in terms of total volume), the remaining years (2002 with 35,627 units, 2003 with 35,469 units, and 2004 with 34,064 units) proved that the C5 had achieved a level of success previously thought unattainable when discussions of a fifth-generation model first started nearly twenty years earlier.

With total C5 production (1997-2004) totaling 248,715 units, the C5 Corvette continues to represent an unforgettable chapter in the history of the brand. The fifth-generation Corvette was responsible for having an enormous positive impact on how the brand was seen around the world. While some might argue that the C5’s styling is dated by today’s standards, the car’s reputation for performance, reliability, advances in technology, ride comfort, driving dynamics, and contention as a truly world-class sports car remain as relevant today as when the car was first introduced nearly two decades earlier. It is still considered by many automotive enthusiasts (and not just Corvette purists) as one of the “most exceptional Corvettes ever produced.”

Author’s Note

While this last bit does not directly relate to the article you just read, I felt compelled to share a personal story that reiterates the lasting impact the fifth-generation Corvette (admittedly a 2001 Z06 in this instance) has had on the Corvette community and how its creation (and inclusion) in the annals of the brand’s history helped define the direction that future iterations of the Corvette would follow.

On August 13, 2022, one of my best friends (I will refer to him here as Billy) and I traveled to Bowling Green, Kentucky shortly after Billy had purchased his first new (to him) Corvette – a 2001 Torch Red Z06 Coupe. Excited about his recent purchase, and realizing that it was less than an hour away from where we both live, we decided to drive to the National Corvette Museum to some pictures of his car (and mine) parked in front of the Museum. Upon our arrival, however, we were disappointed to discover that the Museum was closed, its gates locked, and its parking lots inaccessible.

Disappointed but not disheartened, we jumped in our respective Corvettes (I was driving my 2016 Stingray M7 Z51 Coupe) and made the short drive from the Museum to GM’s Corvette Assembly Plant located at the other end of Corvette Drive (also in Bowling Green, Kentucky). When we pulled up to the plant, we were happily surprised to find a brand new 2023 C8 Z06 convertible parked in the executive parking area in front of the plant! While seeing one of these cars is almost commonplace today, it is important to remember that the eighth-generation Z06 had only just been revealed at that time, and as commercial production had yet to begin on these cars, seeing one “in the wild” was a HUGE DEAL!

After parking our Corvettes and walking over to admire the new Z06, we were greeted by an individual who had come out of the Plant to grab something from his car—which happened to be that very same Z06 convertible! The driver of the new Z06 was none other than Kai Spande, then Plant Director of the Bowling Green Assembly Plant.

Mr. Spande was beyond kind and took several minutes out of his afternoon to “talk Corvette” with Billy and me. After talking at length about the new Z06, about working at the manufacturing plant, and about Corvettes in general, Mr. Spande asked us about our cars. We identified which car belonged to each of us. When Billy mentioned that the fifth-gen Z06 was his, Mr. Spande made a point that impressed both of us and, to this day, serves as one of the best testimonials I’ve ever heard about any Corvette.

He said (and I am paraphrasing, though only to the extent that I didn’t have a means of capturing his comments word for word during our chance meeting): “There are a lot of us, myself included, at the plant who believe the C5 Z06 is still one of the most capable track cars that Chevrolet has ever built. While the newer models may offer more in terms of technology, driving assists, and horsepower, the C5 Z06 is a true drivers car. Many of the staff here at the plant still prefer them – and still buy them – over the newer models.”

Pretty solid endorsement, right?

Mr. Spande’s comments continue to be the best validation of the fifth-generation Corvette I’ve ever heard. And for Billy, I believe it put any doubts he might have been feeling about his new-to-him Corvette purchase to rest. While it is true that Billy has had to put some work into his car in the years that have followed our chance meeting with Kai Spande, he has also had many opportunities to open that car up both on the open road and the racetrack. Having been beside/behind him more than once in such circumstances, I can only say “Best of luck trying to keep up!”

-Scott Kolecki, January 1-19, 2025