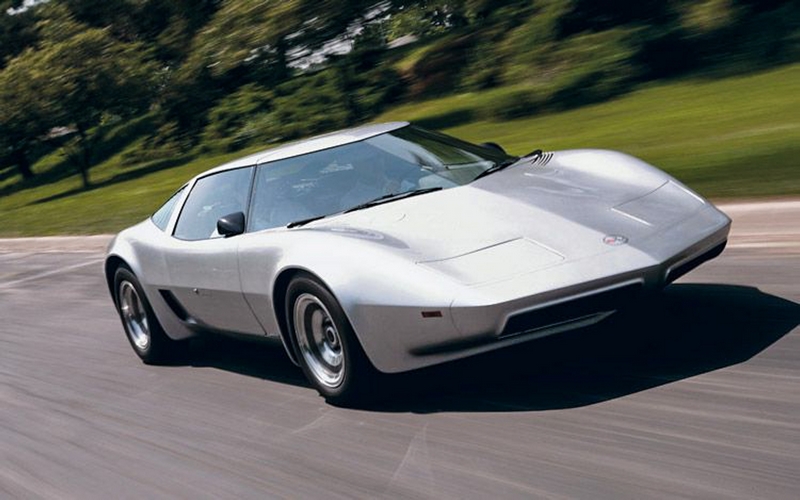

The 1970 XP-882 Corvette Prototype – “The Aerovette”

Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock for the past couple of years, you’ve likely heard that Chevrolet is going to be introducing a mid-engine Corvette later this year as the successor to the C7 Corvette Stingray platform. Corvette enthusiasts around the world are divided by this news – many consider the car to be “revolutionary” while far more feel that the car is “breaking with the traditional front engine, rear-wheel drive” of all Corvettes that came before it.

Before the XP-882

What many people do not realize is that some of the most influential minds behind the Corvette – including “Father of the Corvette” Zora Arkus-Duntov – envisioned a sports car with a mid-to-rear engine platform. Duntov’s dream of a mid-engine Corvette goes almost as far back as the brand itself. His early ventures into realizing a mid-engine Corvette included the development of the CERV I and II (CERV stands for Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle), the former of which served as a test-bed for the independent rear suspension introduced on the 1963 Split-Window Corvette.

Following the CERV II, Chevrolet Engineer Frank Winchell developed the XP-819 Prototype, a rear-engine sports car inspired by the Chevy Corvair. The car featured a body designed by GM Engineer Larry Shinoda and is generally considered one of the earliest rear-engine Corvette prototypes (given that both the CERV I and II were not intended to be a production vehicle prototypes, but rather an experimental platform specifically developed to test emerging automotive technologies.) The XP-819 ultimately proved to be a failure, but its creation fueled the imagination of Duntov. He set to work on creating his own next-generation Corvette prototype.

The XP-882 Aerovette

The Chevrolet Aerovette (originally designated Experimental Project XP-882) was developed in the late 1960’s under the watchful eyes and mind of Zora Arkus-Duntov. Unlike the XP-819, which ultimately proved to have too much rear weight bias, Duntov focused on developing the Aerovette as a mid-engine platform, utilizing a transverse mounting configuration of the car’s V8 engine.

One of the major challenges in the development of the car was the inclusion of a transaxle to drive the rear wheels. Duntov solved this issue during the development of the Aerovette’s predecessor, the Astro II. The Astro II was a race-inspired prototype that also incorporated a mid-engine layout.

His solution was to mate the Astro II’s 454 cubic-inch V8 engine to a Toronado transmission and mount it all transversely to lower its mass. A bevel-gear allowed a prop-shaft to run back through the oil pan into the car’s differential. The design was visionary – and it would pave the way for the future development of all-wheel drive automobiles . It was also prohibitively heavy, adding approximately 950lbs to the car’s overall weight.

Unlike the Astro II, the XP-882 featured a more conventional small-block 350 cubic-inch engine. Despite being lighter than its predecessor, the XP-882 was still a heavy automobile, due in part to the added architecture needed to built the engine and transmission platform in the mid-section of the car.

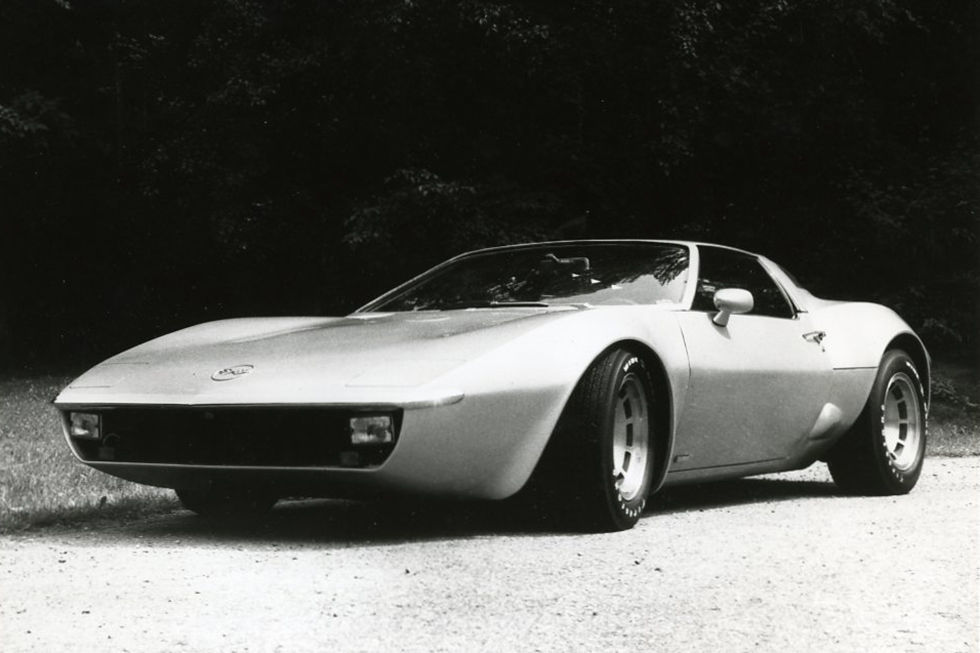

Zora’s engineering group produced two XP-882 prototypes in 1969 before John DeLorean, Chevrolet’s general manager, cancelled the development of the car claiming it was “too impractical and costly.” As DeLorean was shutting down the XP-882 program, Ford announced plans to begin selling the Italian built DeTomaso Pantera. The car, which would be distributed through Ford’s Lincoln and Mercury dealerships, would be available to American markets starting in late 1971.

When DeLorean learned this news, he reversed his decision to cancel funding of the XP-882 and instead ordered Duntov to get the car cleaned up and ready for display at the 1970 New York Auto Show. Ultimately, the car never made it past its prototype stage, despite consumer interest in the brand. Instead, DeLorean and Chevrolet forged ahead with the creation of the third-generation Corvette in its traditional front engine/rear wheel drive format.

However, that is not the end of the Aerovette’s story.

Other Iterations of the Aerovette

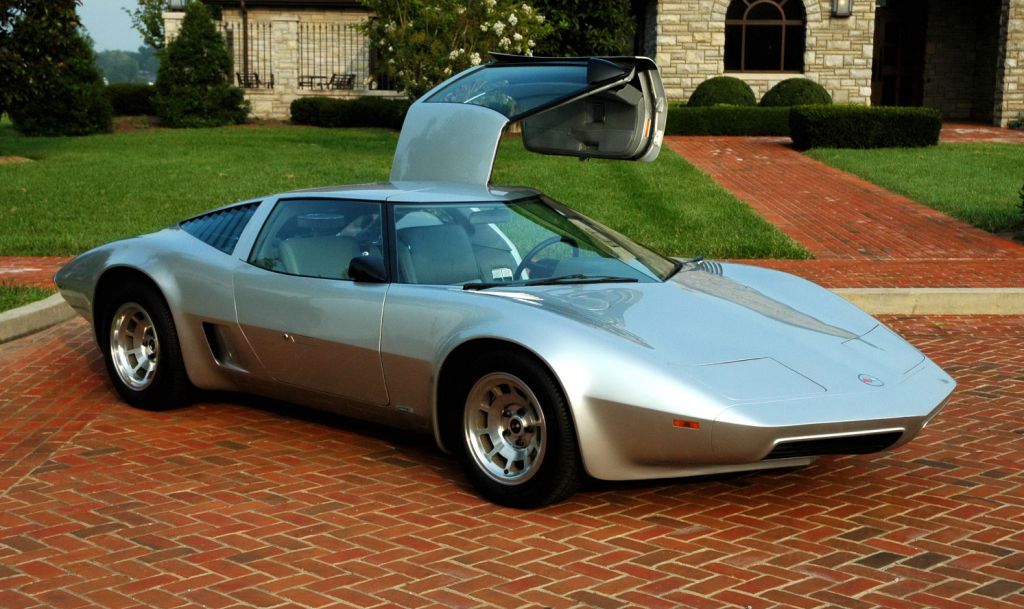

In 1972, DeLorean authorized further development on the XP-882’s chassis. The project was re-named as the XP-895. The car, which was constructed out of aluminum alloy, became known as the “Reynolds Aluminum Car.” This car saw a number of various engine programs, including a hybrid four-rotor, 420 horsepower (313 kW) engine that was developed by fusing two Chevy Vega 2-rotor engines together. The rotary engine development program was later scrapped due to the energy crisis of the early 1970’s.

In 1976, the 4-rotor engine was replaced by a 400 cubic inch (6,600 cc) Chevrolet V8 engine. This latest iteration also featured double-folding gullwing doors. It was at this time that the car officially received the “Aerovette” name, which became retroactive to all iterations of the car (including the XP-882, the XP-895 and the XP-897). The concept car was test-marketed and proved to be a viable and well-received prototype of the next-generation Corvette.

The car was approved for production beginning in 1980. The production version of the Aerovette would feature a 350 cubic inch V8 engine, and it would be priced between $15,000 – $18,000. Unfortunately, the biggest supporters of the Aerovette – Zora Duntov, Bill Mitchell and Ed Cole – had all retired from General Motors before production of the car actually began.

David R. McLellan, would take the reigns a Corvettes Chief Engineer in 1975. He believed that a front engine Corvette would continue to be more economical to build and would provide consumers with a higher level of performance than the mid-engine Aerovette. He decided to abandon the Aerovette program entirely, citing that contemporary imported rear-and-mid-engine cars failed to sell well in the United States, especially when compared to the front-engined Datsun 240Z.

When John DeLorean left Chevrolet in 1973, he did so with the intention of starting his own automobile company. Interestingly, the car that he developed – the Delorean DMC 12 – featured a mid-engine configuration and an overall design not dis-similar to the Aerovette. Although the car was made from stainless steel and not aluminum alloy, the overall aesthetic of the two cars is undeniable, especially when the gull-wing doors are open.

Had the decision to produce the Aerovette not been reversed by McLellan, its likely that a mid-engine Corvette program (in some form or fashion) would be nearing its 4oth anniversary milestone!