Briggs Cunningham – A Man and His Dream

The Early Days of Le Mans

The 24 Hours of Le Mans has been recognized around the globe as the world’s oldest – and most prestigious – endurance racing event ever. Since its introduction in 1923, drivers and teams from around the globe have gathered near the town of Le Mans, France, to compete in the twenty-four-hour endurance race.

The early days of Le Mans were dominated mostly by European racing teams. Because of the costly limitations of transporting vehicles to Europe, American drivers did not make a significant showing at the event. Further, it was commonly agreed that American automobiles did not have the durability or performance capabilities to compete with their European counterparts.

Briggs Cunningham

That perception was challenged in 1948 when Briggs Swift Cunningham, a millionaire sportsman, made the decision to invest a portion of his fortune into developing an American-made racer to compete in the 24 hour event.

Cunningham was excited by the prospect of racing at Le Mans but was also uncertain what type of vehicle to enter in the famous event.

His first attempt at developing a race car resulted in a custom hot-rod built by Bill Frick (the inventor of the Studillac – a Studebaker equipped with a Cadillac engine.) The design for the cars was presented to the organizers of the event and was immediately rejected. An American hot-rod was considered too barbaric for the refined European race.

Around the same time that he was attempting to develop his own race car, Cunningham purchased a Ferrari from Luigi Chinetti, an Italian race driver and former champion at Le Mans. The two forged a friendship and it wasn’t long before Cunningham disclosed his intentions to enter an American-made racer into the 24-hour event.

After Chinetti won Le Mans again in 1949, he extended an invitation to Cunningham to compete in the event and arranged for two American cars to be entered. It was agreed that if Cunningham could finish the race with either car, he’d be invited to return for the 1951 race.

Two 1950 Cadillacs Race at Le Mans

By late 1949, word of Cunningham’s efforts to penetrate the European racing circuit became known amongst American manufacturers, and a sympathetic General Motors offered Cunningham two 1950 Cadillac Series-61 Coupe DeVilles equipped with manual transmissions. Upon acceptance of the vehicle by event organizers, Cunningham purchased both cars from GM. He entered one (No. 3) as a mostly-stock (including air conditioning) car, but stripped the 2-door body off the other and replaced it with a boxy roadster body (No. 2).

Both cars started the 1950 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

The Number 2 Cadillac racer, which the French dubbed “Le Monstre” (the Monster) did not fare well. Cunningham piloted the No. 2 car around the track and succeeded only in driving it into a sandbank. While he was able to eventually dig it out and complete the race, the delay cost him a lot of time. He finished the race in 11th place.

The No. 3 Cadillac fared slightly better and finished the race in 10th place. Given the size and weight of the Cadillac (when compared to the race cars entered by companies like Ferrari, Jaguar and Aston Martin), the results were considered an outstanding achievement for a massive American touring car.

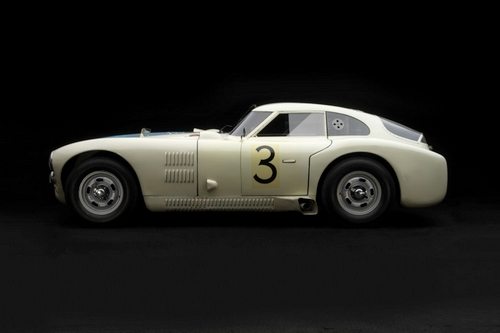

Cunningham’s C-Series Racers

Cunningham would not be deterred by the mediocre results of his first venture at Le Mans. For the next several years, he would work on developing a racer that could compete on the world stage. Such was his commitment that he set about manufacturing his own car – the Cunningham C-Series Racer – and went so far as to build a factory in West Palm Beach where the car could be produced.

The “Cunningham Racers” (as they’re known today) were designed and manufactured around the same time that Chevrolet had begun work on its first production sports car, the Corvette. However, early press on the 1953 Corvette indicated that Chevrolet’s sports car was literally “a bathtub on wheels” and lacked the power and pedigree to compete with anything overseas.

Instead, Cunningham decided to push forward with his own designs. Cunningham’s C-Series Racers were powered by a Chrysler 331 Hemi V-8 engine. These 400 horsepower cars weighed just 2400 pounds and featured a body design reminiscent of the Shelby Cobra (which would not make its first appearance for nearly another decade.) While much more in league with its European counterparts than their Cadillac predecessors, the best results Cunningham’s racers would ever achieve at Le Mans was back-to-back third place finishes (in 1953 and 1954.)

By the late 1950’s, Cunningham had all but abandoned the idea of winning at Le Mans, especially in anything manufactured out of American iron. He had closed the West Palm Beach manufacturing plant and had instead purchased a Jaguar distributorship. While he continued to race, and to fund competitive racing teams, he did so in some of the highest-ranked European automotive fare – Jaguar, Maserati, Lister, Porsche, etc.

Duntov and Cunningham

It wasn’t until 1960 that the Chevy Corvette and Briggs Swift Cunningham would cross paths once more.

Cunningham was approached by Zora Arkus-Duntov. In 1957, the Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA) had facilitated a “gentleman’s agreement” between manufacturers which strongly discouraged them from competing in any type of “factory sanctioned” racing venues. Duntov recognized that an “unofficial” partnership with Cunningham was the best opportunity he’d have to get a Corvette entered into competition at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The “agreement” also meant that auto manufacturers (including any of their employees) would not supply cars, publicize results, advertise speed-related features to their passenger cars, or help (officially) anyone involved in auto racing.

Cunningham, by contrast, was already an accomplished driver and engineer – much like Duntov himself. It made perfect sense to Duntov that Cunningham, who had both the driving prowess and the financial fortitude, should be able to take his beloved Corvette into competition. Moreover, given the major advances made on the Corvette from 1953 to 1960, Duntov also firmly believed that the car was ready to compete on the world stage – and realized that presenting the car at Le Mans would draw a great deal of attention to the Corvette.

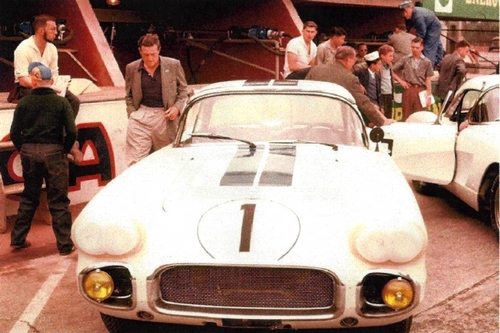

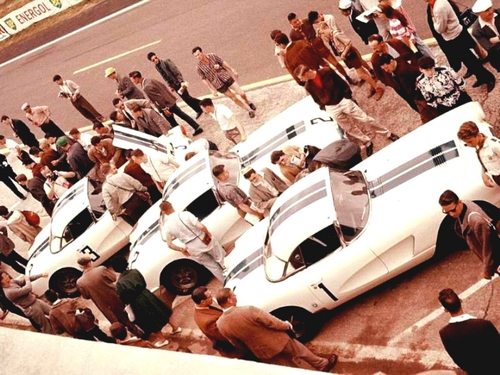

The Cunningham Corvettes

At the end of Duntov’s conversation with Cunningham, it was decided that three Corvettes would be officially entered into the 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans (along with an E-type Jaguar race car, also owned by Cunningham.) The three cars were purchased at Don Allen Chevrolet in Manhattan at a price of $3,910.08 each, and each came equipped with every racing or heavy-duty option offered by the factory at that time.

Each of the three Corvettes featured a 283-cubic-inch, fuel injected engine, a close-ratio 4-speed transmission, a limited-slip differential and sintered-metallic brake linings.

Upon receipt of the three Corvettes, the cars were turned over to Alfred Momo, Cunningham’s chief mechanic, to be fully equipped for race readiness at Le Mans. While it would never be documented, it is also commonly conjectured and believed that Zora Arkus-Duntov also offered guidance/contributed to the modifications made by Momo and his team, though any such assistance would be vehemently denied by both Duntov and General Motors.

As the cars took shape, a number of modifications were made to each of the Corvettes to further prepare them for competition at Le Mans. The three Cunningham Corvettes were:

- Stripped of their grill inserts and chrome trim.

- Their removable hard tops were anchored down and bolted to the car’s body.

- Halibrand magnesium knock-off wheels and race slicks replaced the factory wheels.

- The suspension was bolstered to ensure stiffer cornering (less body roll).

- A 37-gallon fuel tank was installed to provide adequate fuel for the long stints at the 24-hour race.

- Race seats and special instrumentation were installed.

- An adjustable/movable steering column was installed to provide adjustability for the various driver rotations throughout the 24 hour race.

- An external oil cooler and pump were installed.

- The standard aluminum cylinder heads were replaced by new cast-iron versions.

In addition to the modifications made to the cars, Cunningham also recognized that he needed to hire the best drivers if he wanted to be competitive in France. He hired some of the best American drivers of that era and partnered them up to pilot each of the three Corvettes.

The No. 1 car would be piloted by Cunningham along with co-driver William Kimberley, the No. 2 would be piloted by Dr. Dick Thompson (“The Flying Dentist”) and Fred Windridge and the No. 3 car would be piloted by John Fitch and Bob Grossman.

Testing the Corvettes On the Track

With the cars prepared and the drivers selected in early 1960, there was still a considerable amount of time before the cars would need to be transported overseas for competition at Le Mans. Since Le Mans wasn’t until June, Cunningham and Momo both felt it prudent that the cars and drivers gain some race experience prior to the twenty-four race, so they made the decision to enter two of the cars in the 12 Hours of Sebring on March 26th of that year.

The race proved to be both unfortunate and beneficial to the fledgling race team. The No. 1 car, which was driven by Cunningham and Fitch for that event, broke a wheel, flipped over and was out of the race after only 27 laps. The No. 2 Corvette, driven by Thompson and Windridge, lasted until lap 41 before its engine failed, causing the car to retire. The engine was removed from the car and sent to Duntov for analysis.

The No. 1 car’s accident had occurred because the modified wheel hubs had not been strong enough to handle the added G-forces associated with the more rigorous driving. Momo replaced the front hubs and rear half-shafts with stronger units.

The No. 2 car’s engine was returned to Cunningham’s crew from General Motors. The engine had been rebuilt, but Momo noted that it still utilized a bushing distributor bearing, which he had speculated was a likely cause of the initial engine failure at Sebring. Uncertain of the engine’s durability given this possible point of failure, Momo and Cunningham decided to test the car for 24 hours at a private event hosted at Bridgehamption. This time, drivers Grossman and Fitch were selected to participate in the event – allowing Grossman much needed time behind the steering wheel. Although the team discovered several minor issues that they quickly corrected throughout the test run, the car completed the 24-hour test event without incident.

Testing at Le Mans

Just as Cunningham had felt it relevant to test his cars prior to their run at Le Mans, the organizers of Le Mans also hosted a test day for all interested participants. In April, 1960, the No. 2 Corvette (the last one purchased by Cunningham, and the only Corvette not raced at Sebring) was transported to the famous Sarthe circuit to see how it would perform and to determine what kind of lap times it could complete. Running one of the Corvettes at the actual track would also provide Cunningham and Momo with valuable feedback on how the other cars might be expected to perform at Le Mans.

During the test session, one engine failed (reportedly a bent pushrod), but as with the test at Bridgehampton, the results were overwhelmingly positive. The official time sheets from the test session identified that Dick Thompson had been able to turn a respectable lap time of 4 minutes, 28.3 seconds on the 8.36-mile road course, with a top speed of 152 miles per hour on the three-and-a-half mile long Mulsanne straight-away.

Upon completion of the event, the car was returned to the United States for final preparations prior to the 24-hour endurance race. It appeared as though Cunningham’s Corvettes might actually have the mettle to compete (and even win?) in competition at Le Mans.

In early June, 1960, all three Corvettes were sent back to France on the Queen Elizabeth (and discreetly registered as driver John Fitch’s “luggage” to avoid drawing attention to the unique cargo). Upon arrival in Le Havre, France, each of the cars were driven to Le Mans under their own power.

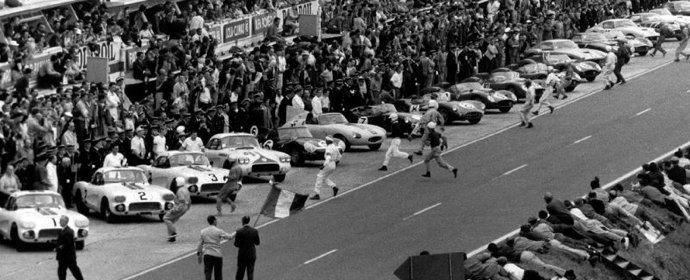

The 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans

On June 25th, 1960, all of the cars competing in the race event were lined up by engine displacement – the cars with the biggest engines placed at the front of the pack. Cunningham’s Corvettes occupied the first three spots. As tradition dictated, all the drivers lined up on the other side of the track and, as the clock reached 4:00pm (local time), the chief racing steward signaled the start.

Drivers dashed across the track, moving quickly to their respective cars, climbed in and fired up the engines with a turn of a key (this was long before push-button ignitions existed) before mashing the accelerator pedal to the floorboards and racing out onto the open track.

For the first couple of hours, the Corvettes maintained position with the rest of the field, demonstrating what Duntov had believed for several years already – namely that the Corvette was capable of competing with the likes of Aston Martin and Ferrari.

Corvette No. 1 & 2

However, misfortune struck as the race approached the third hour of competition.

Just after Cunningham had turned over driving responsibilities of the No. 1 Corvette to Kimberley, a light rain began to fall, causing the track to become dangerously slick. Kimberley approached the “White House” turn (a very aggressive turn on the track) too quickly and skidded off the track before rolling the car over. As the car came to rest, flames leaped from under the hood. Kimberley scrambled to get out of the car, and while unhurt, abandoned the car as it burned. In subsequent interviews with William Kimberley, he is reported as saying that his return to the pits was “the longest mile” he’d ever walked.

The No. 1 Corvette finished just 32 laps before it was officially “retired.”

The No. 2 car fared better (for the first half of the race) in the hands of the “Corvette experts.” Thompson and Windridge, both of whom had considerably more experience driving Corvettes than any of the other drivers on Cunningham’s team, were tasked with operating their Corvette as “rabbits.” Essentially, they were told to drive their Corvette as quickly as possible so as to entice the other competitors to give chase. The concept behind this strategy was that the competition would burn itself out in the effort (either thru driver fatigue or mechanical failure.) Cunningham recognized that this might also mean that the No. 2 Corvette could potentially suffer a similar fate, but the sacrifice might also mean that the other Corvettes could achieve victory.

After No. 1’s accident early in the race, this strategy proved even more critical. The No. 3 Corvette, driven by Fitch and Grossman, would need to pace itself, ensuring that the car maintained both mechanical and driver fortitude.

As the race neared its halfway point, the strategy appeared to be working. The No. 3 car had already moved as high as fourth-place overall in the middle of the night, and was holding ground near the front of the field. As the race moved into the following morning, all members of the Cunningham racing team began to believe that victory at Le Mans might be within reach.

At noon the next day, with just four hours left to go in the race, the No. 2 Corvette’s engine exploded as Windridge thundered past pit lane. Although the car had already fallen out of contention due to an earlier incident which had resulted in the car’s right front fender being damaged (and subsequently repaired on pit lane), spectators had continued to marvel at the impressive display of speed exhibited by the No. 2’s drivers. Now, the team was forced to retire the Corvette due to engine failure.

With two Corvettes out of the running, the crowd’s attention was now focused on the No. 3 Corvette. This American-built sports car was keeping up with the top contenders at Le Mans. For some, this was an outrage, but for most in attendance, this “dark horse” from America was an exciting new contender that brought an element of excitement and uncertainty to a venue that was frequently dominated by Ferrari, Jaguar and Aston Martin.

Corvette No. 3

As the race entered its final hours, the No. 3 car piloted by Fitch and Grossman appeared to be pulling for a top-ten finish as it was running in 6th position. Some even speculated that the car had the potential to win the entire event.

However, fate was a cruel mistress that day. With just a few hours remaining in the race, the No. 3 Corvette started overheating.

To the credit of the team, the car was immediately piloted down pit lane, the engine bonnet propped open and a quick evaluation of the engine performed. Early speculation was that the car had blown a head gasket, though it was impossible to determine with any certainty without tearing the engine apart.

Recognizing that the car was still drivable if they could maintain an operating engine temperature, the team rushed to add water to the radiator and return the Corvette to the racetrack. The challenge was that – per the rules at Le Mans – the team could only add water to the car after they completed 25 laps. However, the car would begin to overheat again after running just two-to-three laps, creating an obvious problem for the team if they planned to try and finish the race.

How was the team to continue racing if they couldn’t provide the engine the water it desperately needed to maintain temperature?

Fire or Ice?

According to racing legend, Briggs Cunningham had always maintained a deep distrust for French Cuisine and had, instead, kept himself refreshed and nourished by eating one of his great loves – ice cream! Cunningham had parked a refrigerated ice cream truck behind the pits (alongside the spare parts, automotive components and other equipment) packed full of his favorite flavors. While this much has been confirmed (as we’ll see in a moment), the story goes that Momo used the ice cream from Cunningham’s truck as cool packing within the engine compartment. He’d have the No. 3 Corvette come into the pits every 10 laps or so, and re-load the engine bay with more ice cream before sending the car back out on the track, dripping melted ice cream as it went.

Most legends are based on some elements of truth, and this one was certainly no exception. Momo did utilize the refrigerated ice cream truck to remedy the overheating issue, but it wasn’t the ice cream he was after. Instead, Momo packed dry ice from the ice cream truck into the engine compartment (the rules said fluids could be added every 25 laps, but came no limitations on the use of other cooling agents). The dry ice would provide adequate cooling between laps, enabling the Corvette to continue on the track long enough to meet the 25 lap requirement, at which point more water would be added to the radiator.

Even with this stroke of genius counteracting the overheating issue, Momo, Fitch and Grossman recognized that the car would still need to be babied to prevent overheating.

The team slowed the Corvette down significantly, maintaining the minimum average speed to prevent being disqualified. Lap times increased to nearly 15 minutes, which was nearly four times as long as it normally took the car to complete a single lap, and it cost the team track position as the car finished its final hours in the race.

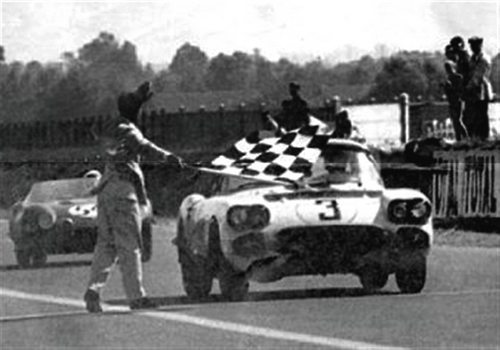

As the clock crossed the twenty-four mark and the checkered flag waved, the No. 3 Corvette driven by John Fitch and Bob Grossman crossed the start/finish line, completing 281 laps, coming in 8th place overall (behind six Ferraris and one Aston Martin).

However, the more impressive accomplishment for the team was that the No. 3 Corvette finished first in the GT Class, which marked the first-ever class win by a Corvette at Le Mans, an accomplishment that would not be repeated for more than forty years.

After the Race

While the accomplishments made with the Corvette at the 1960 24 Hours of Le Mans would prove to be a pivotal moment in Corvette’s history, Briggs Cunningham left Le Mans feeling as though he had failed once more. From his perspective, the cars had failed him on the racetrack, and he vowed never to race a car built by General Motors again. Upon returning to the United States, he gave the three Corvettes to his old friend Bill Frick (who had built the hot-rod Cunningham had first tried to enter in the 1949 Le Mans race).

Before disbanding the cars completely, Momo and crew tore the engine of the No. 3 Corvette down to try and determine for certain what had caused the overheating issue at the track. Although nobody had believed it at the time, Alfred Momo had been right – the bushing bearing supporting the distributor shaft had worn out prematurely, allowing the distributor to advance the spark several degrees, which caused the engine to both lose power and overheat.

While Cunningham may have felt that he had failed at the 1960’s 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Cunningham Corvettes changed the European perception about American automobiles in general, and American-performance cars in particular.

The “success” at Le Mans – while not what Cunningham had hoped to achieve – sparked the imaginations of automotive designers and engineers across the United States. It motivated Zora Arkus-Duntov to return to the Corvette design group and begin working on the development of true, track-capable Corvettes race cars – which would culminate in the creation of the 1963 Corvette Grand Sport (before government pressure would officially end GM’s official involvement with motorsports for the next half-century.)

Even today, as the Corvette C7.R dominates the international racing stage, winning championships both domestically and abroad, there is no question that its involvement at Le Mans today is linked back to Cunningham’s efforts in 1960. Had he lacked the vision and determination to build those early Corvettes and race them at Le Mans, the Corvette might never have evolved into the performance machine that we know and love both on and off the racetrack.

Great story, well-told. Ten years ago, as producer/director, my crew and I chronicalled the story of these historic Corvettes at LeMans in the feature-length documentary, THE QUEST. The story had never been told in his form before or since. We traveled through 13-states coast to coast uncovering the elements to this story. We also spent a week in Europe to film the conclusion of a dream that had been cut short by heartbreak a few years before. View an extended trailer for the film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9991g6q-xw

A well done piece, Scott. Thank you.

I stumbled across it while researching for a book on that very subject — Briggs Cunningham’s 3-Corvette effort at LeMans in 1960. I would love to talk with you about your sources of research.