Mid-Engine Prototypes: The 1985 Corvette Indy Concept, The 1986 Corvette Indy and the 1990 CERV III

Since the introduction of the Chevy Corvette in 1953, there have been a number of Corvette prototypes that featured a mid-engine configuration. From concept vehicles to “almost” production models, the mid-engine Corvette has been in the minds and imaginations of Corvette engineers for generations. The 1964 XP-819 gave the world its first glimpse of a rear-engine Corvette. Just a few years later, Chevrolet revealed the 1970 XP-882, a mid-engine Corvette initially developed by Zora Arkus-Duntov. The XP-882 evolved into the Aerovette and was actually slated for production as the next-generation Corvette. It was intended to succeed the C3 in 1980. However, due to changes in management and the decision to take a financially conservative approach to Corvette manufacturing, production was halted in favor of the far more traditional front-engine, rear-wheel-drive C4 Corvette, which debuted in 1984.

The cancellation of the mid-engine Aerovette program in the late 1970’s caused many Corvette engineers to “dig in their heels” and continue development of a mid-engine Corvette. Just a year after the introduction of the fourth-generation Corvette in 1984, Corvette engineers began development of another mid-engine Corvette Prototype which they believed would be a possible successor to the fourth-generation (C4) corvette. They named the first of these cars the Corvette Indy Concept.

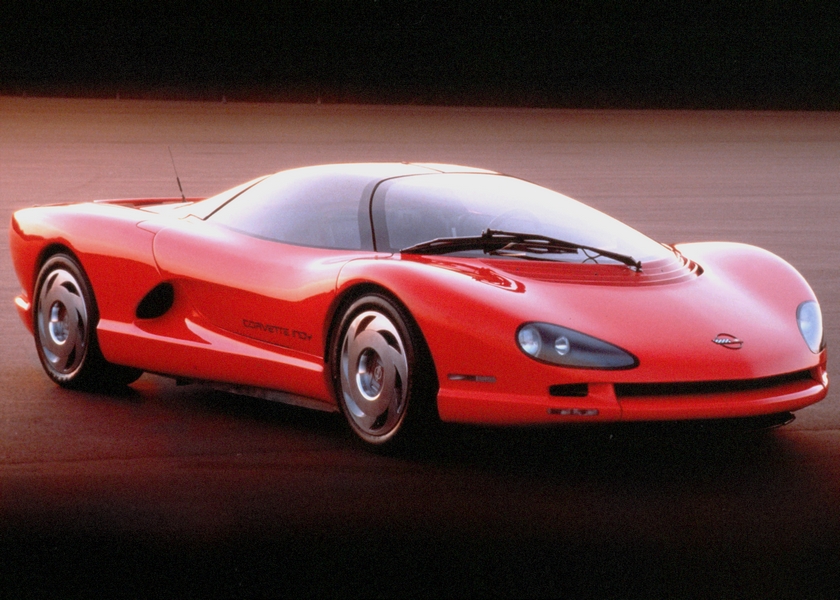

1985 Corvette Indy Concept

The first of these cars was the 1985 Corvette Indy Concept vehicle. It was developed as a “pushmobile,” meaning that it was a non-functioning, full-size clay mockup that was developed to test market interest in the concept. The car featured the same mid-engine configuration that Zora Arkus-Duntov had always envisioned for the Corvette program. Finished in a silver paint scheme, the Corvette Indy Concept was first unveiled at the Detroit Auto Show in 1986. The car itself had a dramatic, swept-back profile. It featured a short snout an elongated rear-end.

While the design was well-received, its dramatic posture was definitely a departure from all Corvettes that had preceded it. However, if you look closely, you’ll note that the car’s overall aesthetic was reminiscent of the fourth-generation Camaro that debuted in 1993. It also featured a wheel concept which evolved into the OEM “turbine” wheels found on the late-model C4 Corvettes beginning in 1991.

The 1986 Corvette Indy

The 1986 Corvette Indy Prototype was developed beyond clay modelling to the point of a fully-functioning, drivable car, though it was clearly understood that this car would never evolve beyond the prototype stage. Like the clay mock-up before it, development of the mid-engine Corvette Indy prototype began in 1985, pulling most of its design cues from its predecessor.

The Ilmor Company, an independent British engine manufacturer which had been established in 1983, began development of a new 2.65-liter IndyCar engine that featured twin-intercooled turbos. Known as the Ilmor–Chevrolet 265, the engine made its debut at the 1986 Indianapolis 500 with Team Penske driver Al Unser. Chevrolet engineers adapted a version of this engine for use in the Corvette Indy Concept, which was so-named because it featured an engine that had been designed for use by Indy race cars.

General Motors Vice President of Design Chuck Jordan took an immediate interest in the mid-engine Corvette Indy. He believed that the car would be an ideal showcase for the emerging electronics and technology markets that were beginning to make inroads into the production car market. He directed the engineering team (which included then-staff-designer Tom Peters) to integrate these new technologies into the next-generation Corvette. He began the process by using Peter’s rendering of the next-generation Corvette concept to determine what (and how much) technology could be packaged into the actual car. Some of these technologies included satellite navigation (which was significant in that it was introduced before global positioning satellites were approved for the civilian market), a CRT (Cathode-Ray Tube) instrument display and an electronic throttle control system.

During the same time this car was being developed, General Motors was also in the midst of acquiring Group Lotus. Jordan recognized that the Corvette Indy presented a unique opportunity to showcase the British automaker’s new Active Suspension technology to the American automotive market. GM also wanted the car to showcase some of its latest home-grown mechanical technologies including their all-new four-wheel steering system along with four-wheel drive. Perhaps most significant of all, Chevrolet utilized carbon fiber and Kevlar construction materials in much of the car, including a carbon tub and body. The Indy’s carbon fiber and Kevlar construction was revolutionary for its time, and it paved the way for how many supercars are built today.

As the car evolved, the Indy race-engine was ultimately abandoned from the Corvette Indy Concept in favor of a 350 cubic-inch V8 engine. The V8 engine was developed and tuned by Lotus. It was installed in the Corvette Indy and, when so equipped, enabled the car to reach speeds in excess of 180 miles per hour and a 0-60 time of under five seconds. This second engine program was used as the powerplant for the production Corvette ZR-1 from 1990 to 1995.

The CERV III

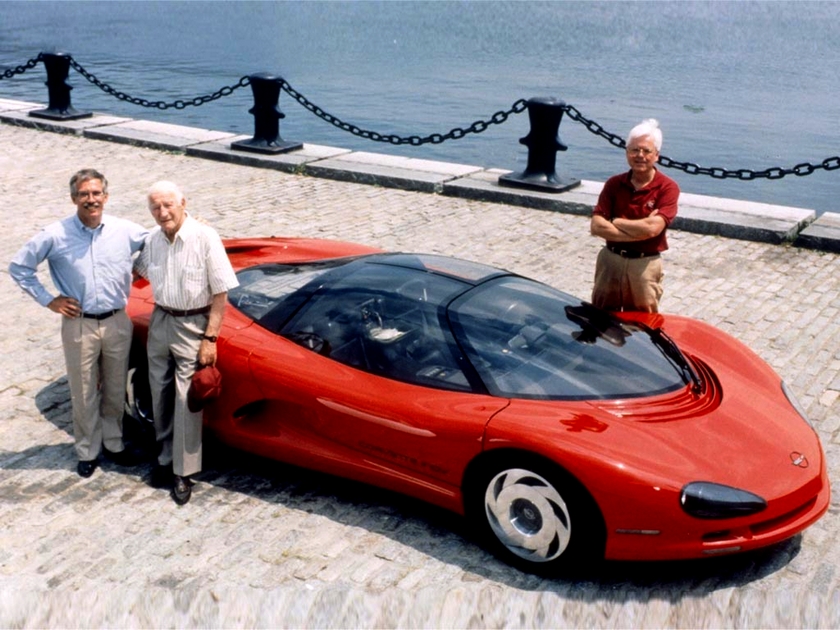

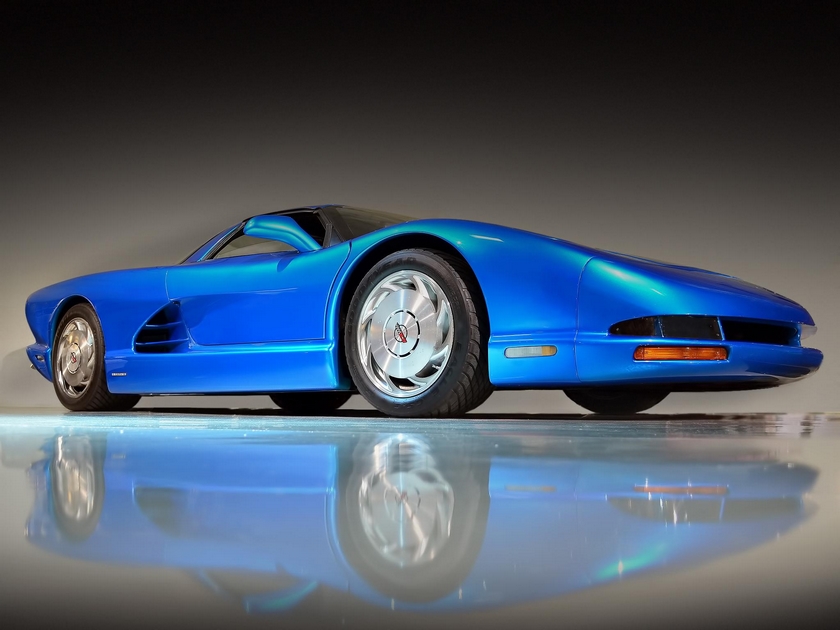

While it was understood that the Corvette Indy Concept would never be fully realized as a production vehicle, it paved the way for the creation of the twin-turbo CERV III. The CERV III (Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle No. 3) was introduced in January, 1990 at the International Auto Show in Detroit, Michigan. Like the latter iteration of the Corvette Indy Concept car, the CERV III was fitted with a 5.7 Liter, 32-valve, dual-overhead cam LT5 engine that featured twin turbochargers. So equipped, the car was rated at 650 horsepower (485 kW) and 655 lb/ft (888Nm) of torque with a documented top-speed of 225 mph (362 km/h).

Despite the size of the new powerplant, the CERV III’s engine was mounted transversely (as it had been in the Corvette Indy Concepts.) The engine powered all four of the car’s wheels through a six-speed automatic transaxle (which was, in reality, a three-speed Hydramatic transmission driving a custom two-speed gearbox.)

The CERV III was developed to the verge of becoming a production vehicle despite being far more sophisticated (and therefore far more expensive to build) than any Corvette that came before it. It was hailed as being the “most advanced Corvette study to date” full of the most sophisticated electronics available at that time. For example, the introduction of electronic computer-controlled systems enabled the return of fuel-injection (which provided higher levels of performance akin to what the old second- and third-generation Corvettes once offered) all the while maintaining better than expected fuel efficiency and low emissions ratings, even when running on commercial grade gasoline.

As with its predecessor, the CERV III was manufactured from carbon fiber with a fiberglass-finish coating. Many of the car’s design elements – including the shape of the car’s roof – served as design cues for the next-generation C5 Corvette, a car which would not be introduced until 1997 (seven years after the introduction of the CERV III.) It featured a more rounded nose and front fender shapes, both of which would influence the final look of the C5 Corvette. The car also included Lamborghini-type “scissor” doors, an active suspension system to keep the car flat during hard braking and cornering, and computer controlled rear steering to tighten its turning radius while also improving high-speed stability. Ultimately, one of the major objectives of the CERV III was to showcase the partnership between the Chevrolet design team and the Lotus advanced racing experience members.

Of course, as with anything this new and advanced, the car carried with it a hefty estimated price of between $300k and $400k per unit. Naturally this cost prohibited any rational discussion about taking the car to production. General Motor’s worsening financial situation, coupled with the fact that the CERV III never formally received funding from GM, meant that the car would not hold much direct sway over the Corvette production-car program of its day.

“The mid engine Corvette Indy series [including CERV III] was interesting in that it used a drivable backbone that tied powertrain and suspension rigidly together with an isolated body,” says former Corvette Chief Engineer David McLellan. “We also had the concept for the transaxle backbone design that became the C5. We reviewed both with the engine guys, and they rejected the structural backbone that bolted the engine rigidly to it as too radical. They thought the suspension loads would break the engine structure. They were probably wrong, but this made it easy for them agree to the alternative proposal. The Corvette Indy series was a Design ‘flight of fancy’ that never made any sense beyond its backbone architecture.”

The ultra-high-tech CERV III concept car ended up being tested at GM’s Milford, Michigan, and Mesa, Arizona, Proving Grounds, as well as at Lotus’ test track in Hethel, England. It was seen at the time as GM’s final try at a production mid-engine Corvette. However, once the decision was made that the C5 Corvette would be introduced as a front-engine car, the CERV III disappeared from public view entirely.