1997 was a great year for car enthusiasts. The Porsche 911 GT1 Straßenversion, a literal race car for the road, became the toys for 20 very wealthy collectors. The last version of the Lotus Esprit, the GT3, was released, as was the first generation of the now legendary Lotus Elise. But most importantly of all, out of Bowling Green, Kentucky, a new generation of Corvette arrived.

The Corvette C5 was a radical reboot of the entire Corvette brand, after a fairly stagnant fourth generation. It had nods here and there to both the C2 and C3 generations, but the most important factor in the C5’s success was that instead of upgrading and iterating on the previous car’s chassis, it was a car that was brand new from the ground up.

A new chassis, using the most modern of materials and designed to withstand immense power. A new LS1 V8 engine way down low in the front. All new transaxle to keep the weight low and central. It was as if they were designing the C5 not as a road car, but as a race car. Many suspected that something was up, that there was a hidden ace in the hole somewhere.

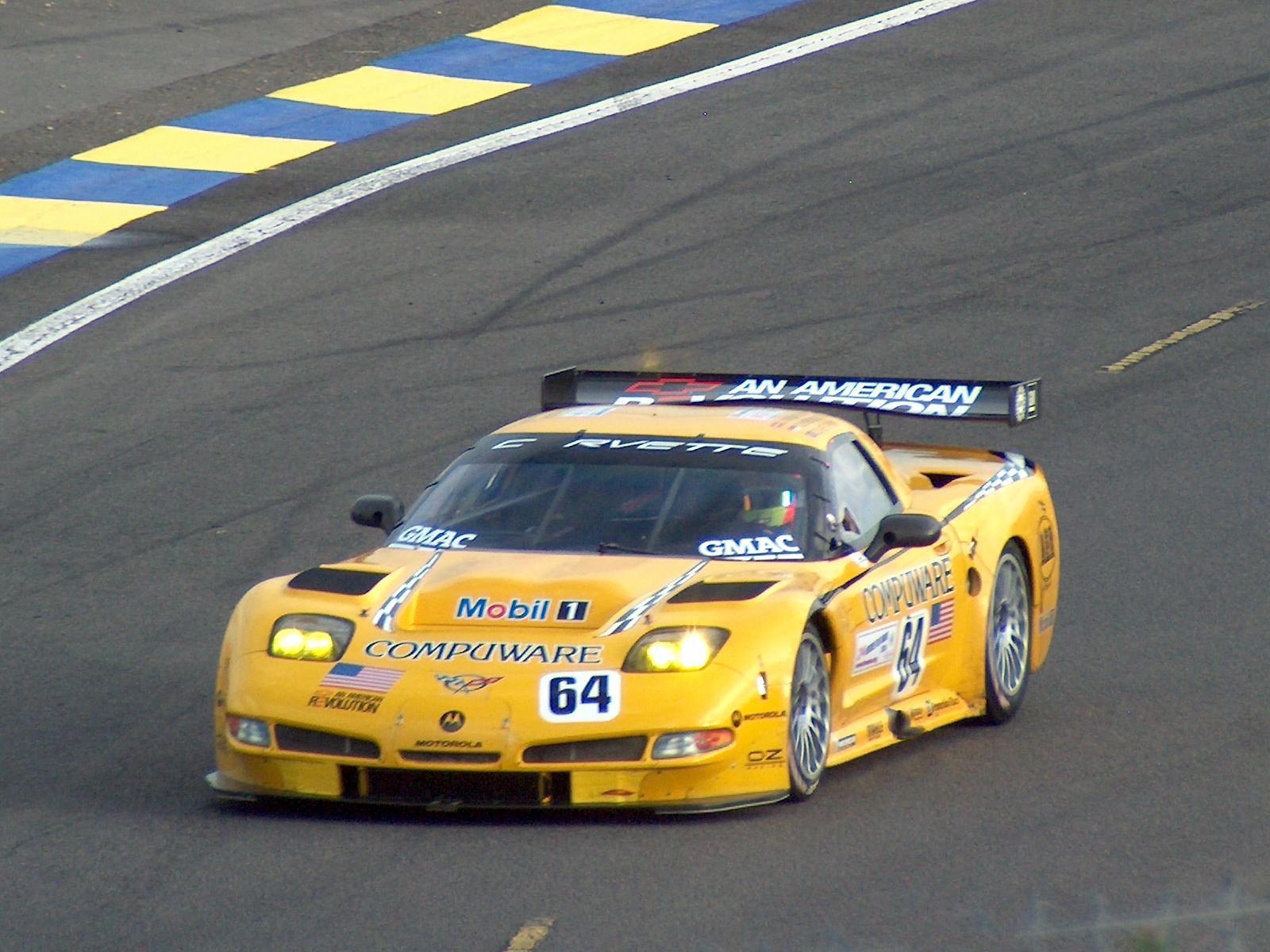

That ace was played in 1999 with the arrival of the Corvette C5.R and the associated Corvette Racing Team, the first works outfit to race a factory car in almost 30 years. While not built on the same chassis as the C5, the C5.R used the same layout, except lengthened and widened, with a monstrous 7.0L LS1.R V8 up front roaring out 610 HP. Developed and built by GM partners Pratt & Miller, the C5.R would make its debut at the 1999 24 Hours of Daytona, where quite a few quirks that only real racing can reveal were discovered, and the highest placed C5.R was 18th overall.

It took a while for all the quirks and bugs to get worked out of the car, but after nearly 24 months of hard work, it was time to line the C5.R’s up at the fabled Circuit de la Sarthe for the 2001 24 Hours of Le Mans.

2001: A Hard Fought Race

There were a lot of expectations placed on Corvette Racing going into the 2001 24 Hours of Le Mans, the 69th running of the great race. It was the first race that the revamped C5.R competed in, with all of the small quirks ironed out and the car performing very well in independent testing. It was high time for the race program to start posting top ten, or even podium position results, as the investment into the Corvette Racing program was not insignificant, and both GM and private investors, and sponsors for the team wanted to see their names in the top three.

Testing: May 6, 2001

The mandatory pre-Le Mans test day, split into two four hour sessions a full month before the race itself proved to be valuable to Corvette, as the 64 Corvette C5.R, racing under the team name Corvette Racing Pratt, with the driving team of Andy Pilgrim, Kelly Collins, and Franck Freon, suffered a steering link failure. This led to an internal investigation, which identified that in very precise conditions, the steering had a chance to fail. Without that initial failure on the test day, there would not have been enough time to identify and repair the issue.

Qualifying: June 13 & 14, 2001

Fast forward a month to qualifying, eight hours divided into four two hour sessions, during which all entrants that were to run in the race had to be within 110% of the fastest car of each class. The Corvette C5.R was able to finally flex its muscles, and for most of the qualifying sessions, the 63 Corvette C5.R, driven by Ron Fellows, Scott Pruett, and Johnny O’Connell, sat in provisional pole position in the LMGTS class.

It was so fast, in fact, that it was only 6 seconds off the pace of the tail end of the LMP675 field, what would later become known as LMP2. Only an absolutely barnstormer of a lap by the 60 Saleen S7-R moved the 63 from pole, and only by a second.

The 64 Corvette C5.R did almost as well, coming in 4th in the LMGTS field qualifying, beaten only by the 60 Saleen S7-R, the other C5.R, and a privateer Viper GTS-R. While the LMGTS field was only about 10 cars strong in the 2001 Le Mans, this was a sign that they were finally seeing the performance and promise of the C5.R coming to light.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans: June 16 & 17, 2001

Corvette Racing had an almighty scare during the morning warm-up and shakedown session that started at 9 AM local time. Although only a 45 minute session, both Corvettes were running well, lapping a few seconds slower than qualifying as this was just a final verification run that the cars were good to go.

Nearing the end of the session, however, the 64 Corvette, which seemed to be the cursed car of the team, suddenly slowed and came to a halt just after the start-finish straight, stopping beneath the famous Dunlop Bridge. Hearts leaped into throats or dropped down to feet as there was rapid radio communication between the car and the pit lane, with the driver reporting a full loss of oil pressure, and had killed the engine the moment the warning had come up and coasted the car to a stop.

The relief was tangible, however, once the 64 C5.R was recovered to the pits, and the first mechanic under the hood noticed that the oil pump’s belt was nowhere to be found. It had snapped under full acceleration down the front straight, and was a quick, easy, and cheap fix to simply fit another belt.

When the race started at 4 PM local time, the 63 and 64 Corvette C5.R’s were able to hold position, but neither soared away from the field or fell back too far. For the first few hours of the race, it was very much about keeping the status quo and being within attacking distances of the Saleen S7-R so that pit stops could be capitalized upon. Then, however, when Ron Fellows began his first stint of the race, the skies darkened and the heavens opened.

During the early part of the race, before the rain came, the 64 Corvette C5.R right on the tail of the 63 C5.R

The rain was torrential, to the point that the ACO, the governing and sanctioning body of Le Mans, deployed the safety cars a few times because it was simply too dangerous to run at full speed when you couldn’t see more than 100 meters down the road. It became less a race about raw speed and skill, and leaned much more into the endurance side of things. The rain would ease or even stop, but the track never fully and completely dried during about 21 of the 24 hours. It would start to dry, and then another rainshower would soak it again.

Throughout it all, the Corvette C5.R’s, despite the curse that hung over the 64 car, ran flawlessly. At one point in the race, the 63, with Fellows behind the wheel, was running fourth overall and leading the LMGTS class. Multiple cars, pushing the limits, would go off track, some catastrophically so, including both Saleen S7-R’s, although one ripped its entire front end off, while the other needed some timely but relatively simple repairs.

To put it into perspective, of the 48 cars of all classes that entered the race, only 20 finished. It was that much of a race of attrition, and the track was that slippery for most of the race. When the sun finally shone brightly and fully again in the afternoon of the 17th, the track finally dried out enough to return to racing on slick tires for the last hour and a bit. By this time, the 63 Corvette was running 7 laps ahead of the 64 Corvette, which itself was 25 laps ahead of the repaired 60 Saleen S7-R. The fight had not so much been against the Saleens and the Vipers of the GTS class, but against the track itself and the weather.

When 4 PM finally hit on June 17, 2001, the 63 and 64 Corvette C5.R’s crossed the line in parade formation, the 64 to the left of the 63 (see the header image for this article), claiming Corvette’s first 1-2 class victory at Le Mans, and coming in 8th and 14th overall. During the remainder of the 2001 season, Corvette either placed on the podium or won 10 out of the 14 other endurance events, solidifying the C5.R as a high performance, and more importantly reliable, race car to carry the Corvette name back to the top step.

2002: Once Is a Good Thing, Twice Is Better

Corvette Racing returned to Le Mans in 2002 with mostly the same teams, and opted to keep the same numbers for their cars, 63 and 64. Ron Fellows and Johnny O’Connell returned to drive the 63, with new driver Oliver Gavin replacing Scott Pruett. Andy Pilgrim, Kelly Collins, and Franck Freon returned to drive the 64. This year, testing went off without a hitch, with no gremlins or quirks about the car to be smoothed out. Just smooth, consistent lapping, a few adjustments to the suspension to get it just right, and a few more laps to test it out.

Qualifying: June 12 & 13, 2002

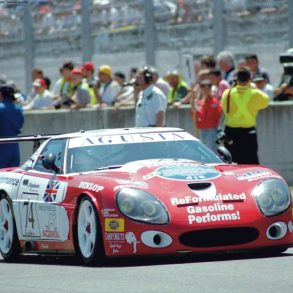

Qualifying was much different, however, as instead of a C5.R leading much of the session, the Ferrari 550-GTS Maranello entered by the legendary ProDrive team surged into provisional pole by more than 4 seconds over the 63 Corvette. Throughout much of the rest of qualifying, the gap was slowly closed, seemingly at a quarter of a second at a time, yet it was clear that ProDrive had done their typical magic on the 550-GTS and it was the class of the LMGTS field.

In the last qualifying session, after a day and a half of blazing heat, the weather cooled, and the 63 Corvette was driven to the absolute limit, placing 2nd in qualifying by 0.8 seconds behind the 550-GTS. The 64 C5.R placed one spot lower than in 2001, in 5th in the LMGTS field, which was filled with Vipers, S7-Rs, Corvettes, and the lone Ferrari.

The 24 Hours Of Le Mans: June 15 & 16, 2002

While the 2001 race was considered a lucky, hard fought win against the elements, no such issues plagued the 2002 race. Not a spot of rain the entire weekend, it was almost all sunshine and dry track. This meant that if Corvette Racing wanted to win back-to-back, they would have to use every ounce of skill that every driver possessed, and drive the wheels off of the C5.R.

At the start, the 63 C5.R and the ProDrive Ferrari set the early standard for the LMGTS field, with the 550-GTS with its screaming V12 rocketing away during the straights, but the C5.R catching it back up through the braking zones and corner exits thanks to the 7.0l LS1.R having enough torque down low to reverse the rotation of the Earth. It was a back and forth battle, but as the hours and driving stints started to pass, the Ferrari was eking out more and more of a gap.

The howling V12 of the ProDrive 550-GTS Maranello, in this video captured in 2020 from the Red Bull Ring in Austria, was simply too much for the C5.R to catch up to for the first half of the race.

Throughout the night, both the 63 and 64 C5.R’s just kept pounding in the laps without issue. There were no leaks, no steering failures, no snapped belts. Pit stops went off without a hitch, no stuck fuel valves, brake changes going smoothly. Yet, the ProDrive Ferrari was just too fast. It was starting to put multiple laps on the Corvettes, and some had already resigned to the fact that it looked like Corvette was going to place in 2nd or lower in the class.

Then the morning came. There is a very common saying about racing at Le Mans, that “Only the results after 24 hours are what matters.”

In the early morning of the 16th, the 550-GTS started to lap slower. The Corvettes were suddenly closing in on the ProDrive Ferrari, and on lap 167 of the race, it pulled into the pits, was quickly taken into the garage to see if anything could be done, and a few minutes later, it was announced that the ProDrive entry had retired from the race.

At this point, both the 63 and 64 Corvettes had a few laps on the rest of the LMGTS field, so the strategy switched from one of full attack to what is termed in endurance racing as “maintenance laps.” In effect, instead of driving the car to the ragged edge, drive it at 9/10ths and maintain your gap to the cars chasing you, but don’t take unnecessary risks.

What surprised all the drivers and the team especially was that throughout the rest of the day, as other cars started to either crash out or retire with mechanical failures, the telemetry from the C5.R did not pop a single error. The only warnings that were shown were for low fuel nearing the end of a stint, but there were no gremlins at all for the entire race. The closest that any other LMGTS car could get to the Corvettes was the French 52 Viper GTS-R, which managed to get within 6 laps of the 64 C5.R, but simply ran out of time to go any further.

Once again, as the checkered flag fell, the C5.R’s crossed the line in parade formation, with the 64 this time to the right and back from the 63. In endurance terminology, both Corvettes had run a “perfect race.” No mechanical issues, no crashes, no spins, no incidents of any kind that were caused by, or affected, the cars.

Corvette Racing had filled out the forms in 2001, but it was in 2002 that the C5.R firmly stamped the page of history, with back-to-back 1-2 finishes at Le Mans, showing that while the first time was lucky, the second time was legit. The Corvette was here, and it was here to stay and make its mark in history.

2004: The Victory That Defined The Legacy Of The C5.R

In 2003, ProDrive returned to Le Mans with a new, updated Ferrari 550-GTS Maranello that absolutely blitzed the two C5.R’s, putting the two Corvettes, who finished on the same lap, 11 laps behind it. While the C5.R’s placed respectably in the GTS field in 2nd and 3rd, for 2004, the last year of the C5.R’s racing career with the new C6.R coming in 2005, General Motors wanted to close that particular page of history with a win.

As with 2002, testing went off without a hitch. The cars were neither the fastest nor the slowest, and proved to be as reliable as ever as they tweaked and tuned the car to the final configuration for the upcoming race.

Qualifying: June 9 & 10, 2004

The Corvettes set the early standard for the first qualifying session, with the 64 C5.R, driven by Oliver Gavin, Olivier Beretta, and Jan Magnussen setting a 3:54.359, a second better than anyone else managed in the morning. The second qualifying session was used by most teams, Corvette Racing included, to fine tune their setups and adjust settings for the more important second day of qualifying.

Third qualifying was extremely challenging, as an overnight rain shower removed quite a bit of rubber from the surface of the track. Despite the challenging conditions of a “clean” track not giving as much grip as a fully “rubbered in” one would, the Corvettes still were improving their times. Much to Corvette’s chagrin, however, ProDrive had brought not one, but two Ferrari 550-GTS Maranellos to the race, with one privateer team running a third 550-GTS, and another team running a Ferrari 575-GTC, which was a Ferrari factory produced car.

One of those 550-GTS’s, the 65 car, obliterated the fastest lap of the 64 C5.R by over a second halfway through the session. Not to be outdone, Oliver Gavin hopped behind the wheel of the 64 and then laid down a 3:49.750, setting a LMGTS class lap record in the process. The 63 car, driven in 2004 by O’Connell and Fellows joined by CART star Max Papis, seemed to be the gremlin car this year, and while it was lapping within a second of the 64, it wasn’t able to beat it.

In fourth qualifying, the final session, it looked like Gavin’s lap record lap was going to seal a pole position for Corvette Racing, and the first time that the 64 qualified better than the 63. That was, until Tomáš Enge, at that time a fresh face Czech racer that had dabbled in Formula One and the ALMS, behind the wheel of the rapidly repaired 66 ProDrive Ferrari 550-GTS that had been damaged early in the session, screamed around the circuit in 3:49.438 with 10 minutes left in the final session. The 63 Corvette, in those same final 10 minutes, managed to better their time and placed 3rd, half a second back from the 64.

The 24 Hours Of Le Mans: June 12 & 13, 2004

The start of the race made for a great show, as the top five cars of the LMGTS class were racing quite literally nose-to-tail for the first half an hour of the race, with multiple attempts at passing, some side by side drag races to the next corner, and a lot of excellent driving making the GTS field the one to watch. At the end of the first hour, the 64 finally managed to pass the leading 66 ProDrive Ferrari to assume the lead.

Soon after, however, Ron Fellows made a rare mistake, sending the C5.R hurtling into the tire barrier at Arnage Corner, damaging the front of the car. He was able to extricate the car from the tires and limp back to the pits, but repairs took almost 15 minutes, dropping the 63 car 5 laps down as the second hour of the race ticked away.

At the end of the second hour, two of the LMP900 top tier Audis hit a patch of oil during the Porsche Curves and slammed into the tire barrier, with one of the ProDrive 550-GTS barely missing them and the tire barrier as it too hit the oil patch and speared off the road.

Due to the dangerous condition, as well as the fact that Alan McNish in the number 8 Audi R8 collapsed in the garage after getting out of the damaged car with a concussion, the race was placed under safety car conditions so that the oil could be cleaned up, the barrier repaired, and the debris cleared from the track.

When racing resumed, the 64 C5.R extended its lead over the second place 66 550-GTS. Jan Magnussen was at the wheel of the Corvette, with Enge in control of the Ferrari, and managed to keep a 17 second gap between the two cars. This was despite Enge setting a storming lap of 3:53.327, the fastest LMGTS lap of the entire race.

As night began to fall and the 64 continued to lead, the 66 Ferrari, in the hands of rally legend Colin McRae, spun at the first Mulsanne Chicane, damaging the clutch in the process. The biggest rival to the 64 had to pull into the pits and spent 8 laps having its clutch replaced.

This allowed the 63 Corvette to assume 2nd place in GTS, which it held for quite a while before a left rear rapid puncture occurred as the C5.R was cresting the rise just before the Mulsanne Kink, which shot the car off the road and heavily into the barriers. The rear of the car took the brunt of the impact, but damage also occurred to the left side of the car. Somehow, Fellows managed to keep the engine on and the car rolling, and was able to limp it back to the pits.

Working their magic, the mechanics for Corvette Racing, the true unsung heroes of racing, were able to repair the 63 in record time, and the car was cleared to resume racing. What had looked to be a race ending crash had been turned into a miracle repair and the C5.R trundled out of the pit lane and back into the race, amazingly only about ten laps down on the 64.

Shortly after midnight, with Magnussen at the wheel, the 64 C5.R received a scare of its own when the LMP1 Audi R8 running in second place clipped the Corvette at the Ford Chicanes right before the front straight. This sent the Corvette into the tire wall, although not too hard. The C5.R still sustained damage and an agonizingly long full lap of the circuit needed to be done before Magnussen was able to drag the car into the pits for repairs.

Unfortunately, this meant that the 66 ProDrive Ferrari in the hands of Touring Car legend Alain Menu took the lead of GTS, and was able to put the 64 four laps down before the C5.R was able to rejoin the race. It seemed that fate was favoring Corvette, though, as the 66 Ferrari was forced to pit with an engine management problem that turned out to be a chunk of rubber in an air intake, and the 64 was able to cut the deficit from 4 laps to 2.5 laps.

Racing hard, the 64 was able to cut that down to just under two laps, catching the 66 550-GTS, before Oliver Gavin, at the precise midpoint of the race in the 12th hour, missed his braking point for the first Mulsanne Chicane and plowed heavily into the tire barriers. Much like Fellows, he managed to keep the car running, despite heavy damage to the front of the car, and limped it back to the pits.

The Corvette Racing mechanics once again worked their magic, and just under 15 minutes later, the 64 emerged from the pits with a fully rebuilt front end. The downside was that the car was now 6 laps down from the 66 Ferrari, and it wasn’t looking like it would be able to recover that deficit in the second half of the race.

Despite heroic efforts, the 6 lap gap was only cut to 5 laps during the night, with the 64 chasing down the Ferrari, the 63 chasing the 64, and the rest of the GTS field spread out. However, fate smiled once more upon the Corvette Racing team.

While Enge was driving the 550-GTS, the left front wheel bearing seized in the Dunlop Chicane, just past the exit of the pits, and exploded, damaging the front splitter and the left front suspension of the Ferrari. It limped into the pits, but the repairs needed over an entire hour to be completed, by which time not only had the 64 taken the lead, but the 63 was able to unlap itself from the 66 Ferrari.

Things went from bad to worse for ProDrive during the morning, and good to great for Corvette overall, when after the 66 550-GTS rejoined in the hands of Menu, it had to return to the pits a lap later to have the new front splitter replaced to correct a handling issue. Then, after Enge relieved Menu during a full service pit stop, on the first lap out, he missed the braking point at Indianapolis Corner and smashed the front end of the car into a tire wall.

The subsequent repairs and time in the pits dropped the 66 Ferrari from 3rd to 4th in GTS, with the 65 Ferrari 550-GTS taking up 3rd. The 64 and 63 were not out of the woods yet, though, as the worrying radio message to both cars was that they could not suffer another crash, or even damage to the cars, as Corvette Racing had used up all of their allowed spare parts.

There was nothing left to fix either car if they crashed, were hit, or suffered a puncture that damaged the body. It meant that the two cars had to be driven fast, hard, but also cautiously.

Maintaining an 11 lap lead over the 63 car throughout the afternoon, the cars, in their final parade finish, crossed the finish line to record their third 1-2 class win, and defined the Corvette C5.R as one of the greatest American racing cars ever made. Three 1-2 class wins in 5 years of attending the great race, and it was the dream finish that GM wanted. It showed that Corvette Racing was not just a bunch of Yanks that had come over to run in a race, it showed that they were there to win, and win they did.