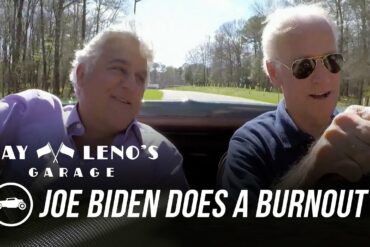

C2 Corvette - “The Sting Ray”

Research & Complete Reference Guide

Basics / The Story / Timeline / MY Research / MY Guides / Buyer's Guide / The Market / Vids & Pics / Latest / Tech Research

The C2 Evolution

There is no doubt that the second-generation Corvette was a revolutionary departure from the original “solid-axle” C1 Corvette. This new Corvette featured fully-independent suspension and a chassis that evolved from the 1959 Stingray concept race car originally envisioned by Brock Yates and fully realized by Bill Mitchell, Zora Arkus-Duntov and Larry Shinoda.

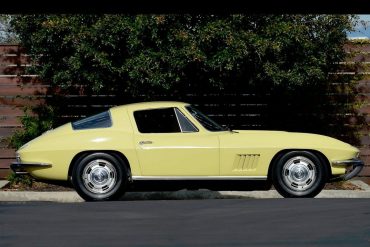

The iconic C2 Corvettes – from 1963 to 1967 – solidified the brand as a serious contender on the world racing stage (even though it was developed in an era when GM was actively participating in the AMA racing ban). The second-generation Corvettes gave us disc brakes, independent suspension, revolutionary engine development, including the introduction of big-block power, and advances in technology on both the interior and exterior of the car. More than that, the design of the C2 Corvettes was simply beautiful “art-in-motion.”

The Sting Ray had a newly designed chassis that featured a shorter wheelbase and a faster “Ball-Race” steering (a name that was developed by the ad copy (advertisement) writers in 1963,) both of which attributed to providing the car with improved maneuverability and handling. A number of items did carry over from the C1 Corvette. This included all four of the small-block, 327C.I. V-8 engines, a trio of transmissions, and six different axle ratios. The engines that were offered for the 1963 Corvette included three carbureted versions; a 250-, 300-, and 340-horsepower variants, as well as a 360-horsepower fuel-injected engine.

In all the iterations of the Corvette that have come and gone since Harley Earl introduced us to the original Corvette in January 1953, there has never been a car more sought after, more revered, more ICONIC, than the second-generation Corvette.

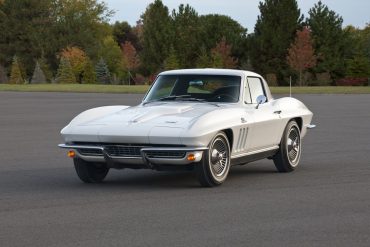

1964 Chevrolet Corvette

1964 Chevrolet CorvetteThe C2 Corvette Story & Details

The birth and evolution of the C2 Corvette occurred amid the successes that General Motors was experiencing at the height of the C1. By the early sixties, as Chevrolet introduced the last of the first-generation Corvettes, there was no doubt – at least among the design team behind the first-generation model – that a second-generation Corvette was imminent.

After all, the 1962 Corvette had shown a 40 percent increase in sales from the previous model year. Better still, the 1962 C1 Corvette – which had more horsepower, better handling, and was physically more appealing than any of its predecessors – had demonstrated to the automotive manufacturing community that their consumers were looking for a quality, performance backed sports car – and that they’d pay a premium to get it.

Still, Corvette’s long term success was not certain. While there was no doubt that the first-generation Corvette was the hottest American sports car on the road in the 1950’s, it was still not quite on par with some of Europe’s best automobiles, especially on the international racing stage. Engine performance and horsepower were certainly no issue – the last few years of the C1 had certainly eliminated any concerns in that arena, but the chassis needed some serious work if it was going to contend with the likes of Porsche and Ferrari.

While Zora Arkus-Duntov, who had been largely responsible for helping the Corvette evolve past its infancy, was certain that the Corvette would continue to evolve into something even greater than its current form, he often found himself defending the Corvette against critics who did not see its potential – especially during the solid axle years.

Given all of this – the certainty that Corvette was gaining additional ground with car enthusiasts year over year, and knowing that the current Corvette had evolved about as far as it could go, Duntov knew that the next Corvette would have to be capable of silencing those critics who questioned whether the Corvette would ever contend with the world’s best.

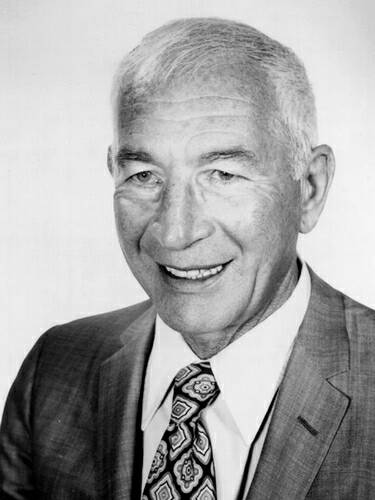

Naturally, designing and developing a successor to the C1 Corvette would not be without its challenges. Even so, it would be the result of these very challenges that would drive designers Bill Mitchell and Zora Arkus-Duntov to create a template from which the second generation Corvette could, and would evolve.

They would do so on the racetrack first, where Corvette had already been banned from being an active participant because of governing automotive laws of the time, but also where Duntov knew the Corvette would have to find its greatest success if it were ever going to be taken seriously as a sports car.

As is common in Corvette’s history, there were obstacles from the very beginning that would have to be overcome before the second-generation ‘Vette could evolve into the car it was meant to become. To start, the Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (AMA) had put a ban in place that prevented automotive manufacturers from building commercially available cars that could/would compete in racing competition.

While a race-ready production Corvette had once been readily available to consumers when it was ordered (and therefore equipped) with the right options, the AMA’s ban (which had gone into effect in 1957) prevented Chevrolet from soliciting these options to prospective consumers. While GM couldn’t officially sanction the production of a race-ready Corvette, it could – and did – continue to offer the options to build one – if the person ordering the car knew which combination of options to order.

Fortunately, there were those within the Corvette’s engineering and development team that were only too happy to help – if unofficially – to promote the advancement of the Corvette as a race car. Zora Arkus-Duntov, who had already been involved with the continued performance enhancements of the C1 since 1955, had ensured that anyone who was interested in building a race-ready Corvette knew the correct options to select. (This was an endeavor he would continue to engage in – unofficially of course – throughout the entire production run of the C1 Corvette.)

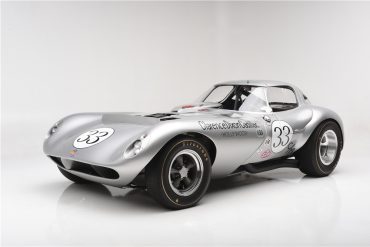

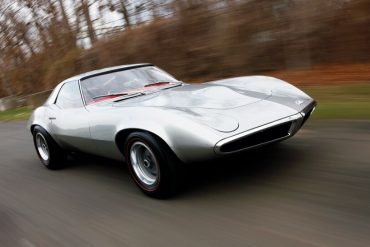

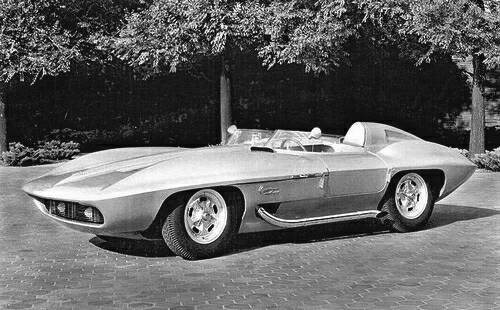

Further, working with Bill Mitchell (one of Corvette’s lead designers), the pair began development of a high performance variant of the Corvette that had been intended solely for the racetrack. By late 1957, the team had developed the Corvette Super Sport, a concept vehicle whose single intent was to run fast and strong at the racetrack.

The Corvette SS had a unique profile that was completely separate from the production model Corvette. The body of the Super Sport Corvette featured a lightweight, magnesium alloy body with a “flying football” headrest that tapered to the rear of the vehicle.

While the elegantly sculpted lines of this new Corvette were not intentionally developed as anything other than a performance alternative to the 1957 roadster, the SS design definitely included styling cues that would readily lend themselves to the next generation Corvette. A wide toothy grille and sleek body lines trailing back to the car’s boat-tail rear end defined an entirely new look for the Corvette – and would be representative not only of the future C2 Corvette, but also the conceptual centerpiece of the “Mach 5” race car (as seen in the 1960’s Japanese animated series “Speed Racer.”)

While the 1957 Corvette SS was successfully track-tested at Sebring by Stirling Moss and Juan Manuel Fangio, the actual race car proved to be problematic, plagued with a number of mechanical issues which impaired its ability to meet the competitive demands for which it was designed. However, before Duntov and Bill Mitchell could set out to correct these issues, the automotive industry’s voluntary racing ban was put into effect, bringing the SS project to an almost immediate end. Fortunately, the car managed to escape permanent demise thanks to the efforts of Bill Mitchell, whose vision and sheer determination would soon give the SS a new life, though it would never formally be used as a race car again.

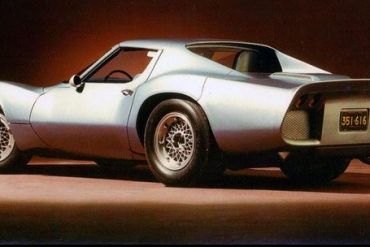

At the same time, the Q-Corvette, also initiated in 1957, envisioned a smaller, more advanced Corvette as a coupe-only model that was initially intended to begin regular production in 1960. Designed in part by Larry Shinoda, it boasted a rear transaxle, independent rear suspension, and four-wheel disc brakes, with the rear brakes mounted inboard.

The exterior styling of the Q-Corvette was developed by Bob McLean, who was also responsible for the original Motorama Corvette’s layout. The design featured peaked fenders, a long nose, and a short, bobbed tail. The Q-Corvette was originally envisioned to be the first of a full line of large rear-transmission cars with which the Corvette would share major components. The idea was that re-locating the transmission to the rear of the car would help balance the front to rear weight distribution of the vehicle, which would provide much better handling. Duntov’s ultimate goal was to develop a mid engine design, but the Q-Corvette was as close as he could get to that goal in the 1950’s.

Ultimately, all of these ideas would be abandoned as the passenger-car line concept was deemed too radical, which ultimately caused the Q-Corvette to suffer the same fate. Since there would be no high-volume production cars from which to borrow components, the Q-Corvette (which would have had a far more limited production run) would have been prohibitively expensive to manufacture. Even with the AMA ban in place and the Corvette SS and Q-Corvette projects abandoned by General Motors, Mitchell still felt compelled to move forward with the development of the Sebring SS Corvette. Using his own money and without the blessing of General Motors, Mitchell decided to transform the test mule into the race car that both he and Duntov felt it was meant to become.

Even more remarkable, Mitchell planned on campaigning his new design under a completely unique banner. Using the ill-fated Q-Corvette concept vehicle as a template, Mitchell adapted lines from this earlier design into his Super Sport’s exterior, creating an entirely new open body layout. Larry Shinoda also contributed to the car’s sleek, new appearance, and helped Mitchell give birth to what would quickly come to be known as the Stingray Special.

Mitchell’s development of the Stingray Special occurred at the “Studio X” special projects area at the GM Tech Center in Warren, Michigan. While it did retain some of the lines of the original SS design, the Stingray had somewhat more rigid lines, more linear styling, and included a pronounced crease line that wrapped around the entire car. It also featured exaggerated wheel flares on all four fenders above the wheel openings. Lastly, it now showcased side-pipes that protruded from just behind the front wheels, ran along the side of the body and ended just ahead of the rear wheels.

For his part, Zora Arkus-Duntov was focused on ensuring that the Stingray would be a successful racer, and he would accomplish this by improving the chassis and mechanical components, just as he had done with the C1 Roadster a half decade before. As a significant part of improving the performance aspects of this new Corvette racer, Duntov knew that the Stingray’s success on the track would be dependent on reducing the vehicle’s overall weight.

Further, developing and installing the right drive train would be vital. So, for the Stingray, Duntov selected a fuel-injected 283-cubic inch V-8 engine which produced 315 horsepower at 6,200 rpm. The 283-cubic inch V-8 also showcased a “Duntov” crankshaft that, while very durable, also aided in weight reduction within the engine. It was rumored that this Stingray could hit 60 miles per hour from a standing start in just 4 seconds.

Word quickly spread of the new Corvette’s performance potential, and this attracted some of the top names in racing to find out first hand what the new Stingray was truly capable of. Dr. Dick Thompson, one the SCCA’s (the Sports Car Club of America’s) top Corvette contenders, stopped by to visit Mitchell’s design studio, took one look at the amazing new race car, and immediately announced that he wanted to drive the car in all C-modified events for that season. Although this class was almost exclusively reserved for Europe’s elite automotive manufacturers, Thompson shocked everyone, including Bill Mitchell, by out-running and outperforming the competition. Thompson regularly took the Stingray Special to victory lane and went on to win the Corvette’s only championship season in 1960.

Although Mitchell and Duntov succeeded in developing a true race-car variant of the Corvette, this car’s time on the track would ultimately be short-lived. Because Mitchell had more-or-less developed this car on his own, and because Chevrolet was an active participant in the AMA‘s racing ban, there was no source of sponsorship to support any sort of racing team. Mitchell did sponsor his own team for a short period of time, the financial burden proved too great and the Stingray Special’s racing career was over almost before it had really started.

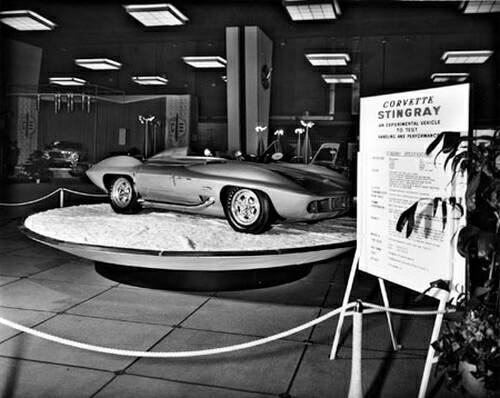

Still, even as that chapter of the Stingray drew to a close, Mitchell modified it and exhibited the car as an experimental show car which he boasted was “built to test handling ease and performance.” Even though the Stingray Special had started its life as a racer, Mitchell saw an opportunity to develop it into something far greater. Like Duntov before him, Mitchell knew that the evolution of the Corvette would occur as much on the racetrack as it did on the open road.

In that way, creating the Stingray Special had actually helped Mitchell to develop a second generation Corvette prototype from which development of a production model could occur. Ironically, the Stingray Special would never carry either the Chevrolet or the Corvette designations, although it would be identified and labeled a Corvette on its subsequent tour as a show car. The car – which had been reworked to show quality – was debuted at the Chicago Auto Show on February 18, 1961, and the response it received was overwhelmingly positive. During its tour, the car made quite an impression on the public, and there was considerable speculation that the Stingray Special was actually being shown as a preview.

Bill Mitchell, Lead Designer of the Second-Generation C2 Corvette Sting Ray. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Bill Mitchell, Lead Designer of the Second-Generation C2 Corvette Sting Ray. (Image courtesy of GM Media.) Zora Arkus-Duntov, the “Father of the Corvette.” (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Zora Arkus-Duntov, the “Father of the Corvette.” (Image courtesy of GM Media.) The 1957 Corvette Super Sport. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The 1957 Corvette Super Sport. (Image courtesy of GM Media.) The 1957 Corvette SS with Zora Arkus-Duntov at the wheel. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The 1957 Corvette SS with Zora Arkus-Duntov at the wheel. (Image courtesy of GM Media.) The 1957 Corvette speed test. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The 1957 Corvette speed test. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Larry Shinoda, one of the lead designers at GM “Studio X”. He was responsible for the design of the Q-Corvette. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Larry Shinoda, one of the lead designers at GM “Studio X”. He was responsible for the design of the Q-Corvette. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

1963 Was The Most Significant Corvette Model Year.

There is a lot to back up that bold statement. The changes seen were revolutionary. The iconic C2 Corvettes – from 1963 to 1967 – solidified the brand as a serious contender on the world racing stage (even though it was developed in an era when GM was actively participating in the AMA racing ban). The second-generation Corvettes gave us disc brakes, independent suspension, revolutionary engine development, including the introduction of big-block power, and advances in technology on both the interior and exterior of the car. More than that, the design of the C2 Corvettes was simply beautiful “art-in-motion.”

When developing the 1963 production-model Corvette, designers included built-in adjusting mechanisms for the bottom seat cushions. Early 1963 Corvettes had under-seat depressions, which was developed for tool storage. However, this feature was removed by the middle of the 1963 production run.

DID YOU KNOW?

Bill Mitchell and the Stingray Special. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Bill Mitchell and the Stingray Special. (Image courtesy of GM Media.) The Corvette Stingray Special. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The Corvette Stingray Special. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Dr. Dick Thompson in the Stingray Sport at the Marlboro Motor Raceway, 1960.

Dr. Dick Thompson in the Stingray Sport at the Marlboro Motor Raceway, 1960.

The Stingray Special made its public debut at the 1961 Chicago Auto Show on February 18, 1961.

The Stingray Special made its public debut at the 1961 Chicago Auto Show on February 18, 1961.

Zora Arkus-Duntov and the CERV I (Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle.) (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

Zora Arkus-Duntov and the CERV I (Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle.) (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The CERV I (Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle) being piloted by Zora Arkus Duntov in 1962. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The CERV I (Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle) being piloted by Zora Arkus Duntov in 1962. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

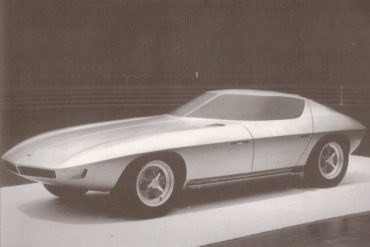

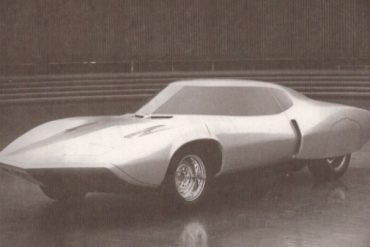

The XP-720 Corvette Prototype.

The XP-720 Corvette Prototype.

Stingray Special was the direct inspiration for the final design of the C2. (Image courtesy of GM)

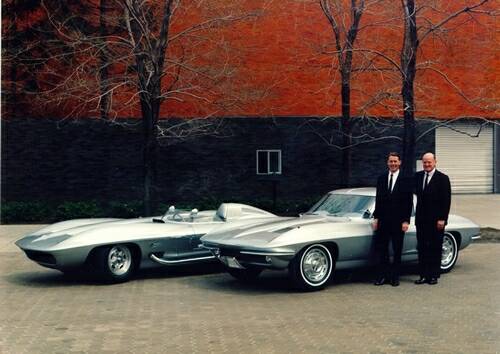

Stingray Special was the direct inspiration for the final design of the C2. (Image courtesy of GM) The evolution of the C2 Corvette began with the Stingray Special and the Corvette Super Sport. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The evolution of the C2 Corvette began with the Stingray Special and the Corvette Super Sport. (Image courtesy of GM Media.) The front hood of the second-generation Corvette featured faux vents that were a throwback to the original Stingray Special.

The front hood of the second-generation Corvette featured faux vents that were a throwback to the original Stingray Special.

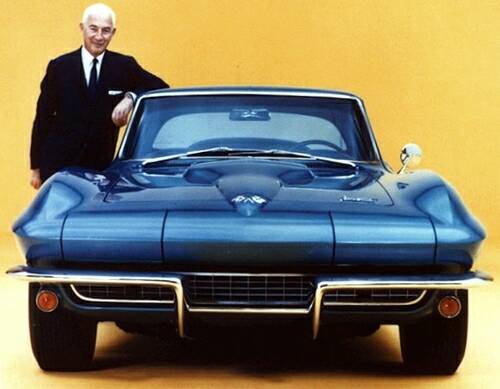

The 1963 Corvette was considered a massive triumph by Zora Arkus-Duntov. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)

The 1963 Corvette was considered a massive triumph by Zora Arkus-Duntov. (Image courtesy of GM Media.)The C2 Corvette Taking Shape

From its inception, the second generation Corvette would be a departure from its predecessor. Duntov had visions of building a contender to the best Europe had to offer, while Mitchell considered the second generation Corvette to be his pet project – in large part because of the time and monetary investment he had put into the Stingray Special. In fact, Mitchell dubbed the second generation project the “Sting Ray”, which he named after the earlier race car of the same name (although the name would now be spelled out as two separate words.) It would also be the first Corvette to bear Mitchell’s signature.

At the same time, Duntov, along with other GM engineers, had become fascinated with mid-engine and rear-engine automotive designs, which was probably inspired after Duntov witnessed the successes that Porsche had experienced in their own rear engine automobile designs.

The decision to pursue this type of design was also likely encouraged by Ed Cole, who had championed a rear-engine design for Chevrolet’s first compact car – the Corvair. It was during the Corvair’s development that Duntov took the mid/rear-engine layout to its limits in the CERV I (Chevrolet Experimental Research Vehicle) project. A rear-engine Corvette was actually considered, though briefly, between 1958 and 1960.

Development had progressed as far as a full-scale mock up designed around the Corvair’s entire rear-mounted power package, including its complex air-cooled flat-six engine to serve as an alternative to the Corvette’s water-cooled V-8 engine. Once more, the design was constrained by the budgetary realities. Recognizing that a rear-engine Corvette was simply “too big of a step ahead” the concept was abandoned and the design team behind the second generation Corvette decided instead to incorporate a conventional front-engine, rear wheel drive drivetrain layout into the new design.

While Duntov did have his dreams – he also had a solid focus on what the next-generation Corvette had to provide. In a memo that he penned to Harry Barr in December, 1957, Duntov wrote: “We can attempt to arrive at the general concept of a new car on the basis of our experience, and in relationship to the present Corvette. We would like to have better driver and passenger accommodation, better luggage space, better ride, better handling, and higher performance. Superficially, it would seem that the comfort requirements indicate a larger car than the present Corvette. However, this is not so. With a new chassis concept and thoughtful body engineering and styling, the car may be bigger internally and somewhat smaller externally than the present Corvette.”

The Sting Ray Corvette really began to take shape in the fall of 1959, when elements from the Q-Corvette and Mitchell’s Stingray Special racer would be incorporated into an experimental project dubbed XP-720.

The XP-720 was born in the fall of 1959 in the cramped basement area of General Motors Styling, known as “Studio X” and home to Bill Mitchell’s right-hand man, Larry Shinoda. Shinoda, who would aid Mitchell in drafting the final body design of the XP-720 from earlier design cues (including elements from his own Q-Corvette,) shared Mitchell’s vision that driver comfort was a key to the design process, and that transforming the Corvette into a coupe was the key to the XP-720 design image.

XP-720 would become the design program that would ultimately lead directly to the production 1963 Corvette Sting Ray. In development of the XP-720, one of the leading design considerations included improved passenger accommodations, increased luggage space, and superior ride and handling over previous Corvettes. Duntov would personally ensure that the latter two of these goals received the greatest emphasis.

In starting the design of the XP-720, elements of the Sebring SS, the Q-Corvette Coupe, the Stingray Special, and the CERV I were all incorporated. Passenger placement was located moderately far to the rear of the vehicle so that the engine/transmission package could be located somewhat behind the front wheel centerline (in a “front mid-engine” position). This placement would allow for optimum weight distribution – which was the same reasoning that had guided McLean on the layout of the original 1953 Corvette. The car’s center of gravity was deliberately kept low in the interest of both handling and ride quality, ending up just 16.5 inches above the road, which was considerably lower than the C1 Corvette‘s 19 inch center of gravity. A side consequence of this decision also meant that the ground clearance of the car was lowered to a mere five inches.

In an attempt to improve the car’s handling characteristics, the location of passenger seating was placed within the boundaries of the automobile frame, instead of atop it as they had been with the C1. By making this modification to the car design, the car’s wheelbase was trimmed four inches to a total of 98 inches. Other notable structural design changes included replacing the 1950’s X-brace frame design with a new ladder-type frame design that included five cross members.

The introduction of the new frame design provided greater torsional rigidity. It also allowed the driveline to ride low and fairly close to the car’s longitudinal center. The additional structural rigidity was deemed a necessity for several reasons. First, Duntov was adamant that the new Corvette would showcase a full independent rear suspension, which would produce higher lateral stresses than any previous Corvette had ever experienced. Second, more powerful engines were already in the works for the second generation Corvette, and the car would require a frame that could withstand the torsional demands put on it as increased power was transferred to the rear axles.

Duntov’s independent rear suspension was simple yet effective. It consisted of a frame-mounted differential with U-jointed half-shafts tied together by a transverse leaf spring – a design which had been derived from the CERV I concept. These half shafts functioned like upper control arms. Rubber-cushioned struts carried the differential, which reduced ride harshness while improving tire adhesion, especially on rougher road surfaces. The transverse spring was bolted to the rear of the differential case. A lower control arm extended laterally and slightly forward from each side of the case to a hub carrier, with a trailing radius rod mounted behind it. These lower arms controlled vertical wheel motion, while the trailing rods took care of fore/aft wheel motion and transferred braking torque to the frame. The shock absorbers remained the same, conventional twin-tube units.

The introduction of Duntov‘s independent rear suspension was an important advancement in the weight reduction of the second generation Corvette. Given that the 1963 Corvette would continue to utilize the first-generation Corvette’s outboard rear brakes, the new rear suspension array delivered a significant reduction in un-sprung weight. Despite its many benefits however, Duntov met with a great deal of resistance after the initial development of the rear suspension was complete. Production costs of the new suspension were deemed prohibitively expensive by GM executives, but Duntov insisted that the suspension would vastly improve the ride quality and the handling of the new Corvette. He sold GM‘s top brass on the idea by assuring them that the new Corvette would sell 30,000 units in its first year.

While the rear suspension of the new Corvette was a radical advancement over the earlier model, the front suspension remained largely unchanged. It continued to feature unequal-length upper and lower A-arms on coil springs concentric with the shocks, plus a standard anti-roll bar.

Steering also remained the same, utilizing the conventional recirculating-ball design, although its gear ratio was modified to a 19.6:1 overall ratio (from the previous 21.0:1. A new hydraulic steering damper (essentially a shock absorber) was bolted to the frame rail at one end and to the relay rod at the other. This damper helped absorb road bumps before they reached the steering wheel, which would help provide drivers a smoother ride. Additionally, hydraulically assisted steering would be offered as an option for the first time on a Corvette, offering a faster 17.1:1 ratio, which shortened lock-to-lock turns from 3.4 revolutions of the steering wheel to just 2.9. However, this option was only available to those 1963 (and later) second-generation Corvettes that did not feature the two most powerful engines – namely the 340 and 360 horsepower 327 cubic inch V-8 engines – that were to be offered.

Although the Stingray Special’s basic design would serve as the inspiration for the second-generation Corvette, the design needed refinement. The Stingray Special was an open cockpit roadster, as were the Corvettes it had evolved from, but the styling team that was assigned the task of designing a production model version of the Stingray Special into a production had turned to the Q-Corvette and XP-720 mock-ups for inspiration. Both of these later vehicles featured a hardtop design, which was ultimately the direction the design team was focused on – and both of these concepts looked remarkably like Mitchell’s Stingray racer fitted with a fastback roof.

By 1960, the designers of the second-generation Corvette had developed a fully functional “space buck” (a wooden mock-up created to work out the interior spaces of the car design). By April of the same year, the styling of the production coupe was effectively complete, and by November, the interior of the coupe – including the dashboard and instrument panel layouts – was complete. With the design work finished on the coupe, designers wasted no time turning their attention to developing a new vision of the Corvette Convertible, including the design and development of a new detachable hardtop. For a brief period of time, Corvette designers even considered the development of a four-seat Corvette coupe. The four-seat concept was developed to the point of a full-size mock-up, but never made it to production.

Even upon casual inspection, there was no question that the Sting Ray was a complete re-imagining of the C1 Corvette. This made it all the more fitting that the car’s transformation would include the introduction of the first ever Chevrolet Corvette coupe. The car was a streamlined fastback that looked both intensely aggressive and unquestionably aerodynamic. It also showcased a unique styling feature that had never been seen on an American production automobile before – a divided rear window.

This feature had been previously introduced on the Oldsmobile Golden Rocket show car in 1956. It had also been considered as a new feature for an all-new 1958 Corvette, though that project got scrapped due largely to the sales obstacles Chevrolet was still trying to overcome with the existing Corvette of the day. Still, Mitchell thought enough of the design to resurrect it from almost certain oblivion when laying out the conceptual ideas for the 1963 Corvette.

The basic shape of the window, a compound-curve “saddleback”, had actually been conceived by Bob McLean while working with Larry Shinoda on the Q-Corvette. The split window proved to be one of the more controversial design elements for that year’s Corvette, with the controversy being most heated between the Corvette’s collective designers – Zora Arkus-Duntov and Bill Mitchell. On one hand, Duntov was opposed to the design because he believed it would hamper road safety by obstructing visibility out the rear window. Mitchell, on the other hand, argued that the rear window was an integral part of the design and it gave a unique, distinctive, one-of-a-kind look to his new Corvette. While not all Corvette fans agreed with Mitchell’s design philosophy, one thing was certain, the second-generation Corvette would not be mistaken for anything else that year.

The front hood of the car was long and flat, save for a bullet shaped bezel that started at the center of the car’s front end and ran the length of the hood before ending abruptly at the front windshield cowling. Cut into the hood on either side of this swept-back bezel were two faux vents. The vents, originally intended to be functional (but nixed because of cost restrictions) were another throwback to the earlier Stingray Special race car design, in which these same vents (though substantially longer than those installed on the production car) were functional.

In some ways, cutting the functionality of these vents from the final design proved doubly beneficial. In addition to being a manufacturing cost savings, the functional version of the vents would have caused warm engine air exiting from the top of the hood to flow right back into the cowl intake for the new windows-up interior ventilation system.

The rear decklid was actually a bit of a misnomer, as there was actually no separate decklid to speak of. Instead, the body molding of the new Sting Ray included a single body panel that wrapped from one beveled fender to the other, and included the rear fenders, the decklid, the B-pillars and the cutouts for the rear split-window. However, in the center of that panel (where a decklid would have normally resided), the designers had cut in a large, round deck emblem that featured the traditional, though slightly modified crossed-flags emblem that had become synonymous with Corvette in the previous decade. This deck emblem was hinged to double as a fuel filler flap, which replaced the previous model’s left-flank door.

The C2 Corvette Model Timeline

1963 Chevrolet Corvette Split Window Coupe From Mecum Auctions

1963 Chevrolet Corvette Split Window Coupe From Mecum Auctions1963 Corvette

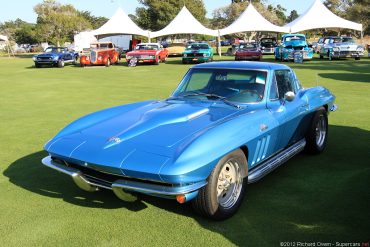

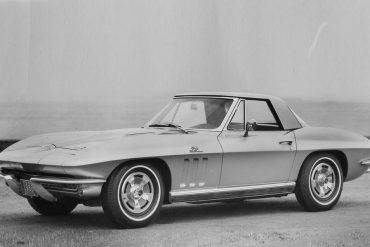

The styling changes alone were earth shattering. If a UFO landed next to a Corvette when it was introduced in 1963 it could have garnered more attention, but maybe not. It had an aggressiveness that still would not be considered brutal, all the while featuring improved aerodynamics. The chassis also saw significant changes, so there was a lot more going on in 1963 than just an updated shape. The new independent rear suspension made a huge difference in every performance area, with improved ride and driving experience as part of the bargain.

© Bring a Trailer

© Bring a Trailer1964 Corvette

Updates for 1964 were minimal. The biggest development was the elimination of the split rear window. Even those who advocated the split window concept admitted that it had drawbacks. Also gone for 1964 were the fake hood vents. The hood indentations remained however although word is that the 1963 faux vents will not fit on the 1964 hood. Perhaps GM figured that the incredible performance the Corvette Stingray offered made enough of a statement. Another change was the added functionality of the air outlet to the right of the driver's door on the coupe. For 1963 they were closed off, represented by a small indentation. A small fan was added to boost airflow but it was only minimally effective and the whole idea was dropped by 1966. Updated body mounting methods and other changes improved interior noise. The overall build quality, long a legitimate Corvette complaint, was improved. There were engine improvements for 1964. The base motor (250 hp) and the upgrade L75 mill (300 hp) were unchanged but the L76 went to 365 hp (previously 340 hp) and the top dog L84 fuel injected model was now 375 hp, up from 360 hp due to revised heads, camshaft and bigger valves. All 1964 motors were 327 cubic inches.

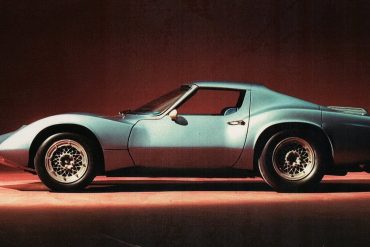

1965 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray

1965 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray1965 Corvette

A long desired and needed upgrade - disc brakes - became standard equipment. The good news is that they appeared on all four corners, not just the front as was common practice of the day. Racers were particularly happy with this latest development as they had long been suffering with drum brakes. Although special sintered metallic linings had been available, fade under racing conditions was still a problem. Jaguar had been offering four wheel disc brakes on their more expensive E-Type and it wouldn't do for the Corvette Stingray to be playing second in any area. The unloved drum brakes were still available as a deletion credit (RPO J61, -$64.50) and 316 1965 Corvette Stingrays were so equipped.

A new Corvette era was ushered in when a leading edge class of engine, fondly known as the "Big Block" was introduced late in the 1965 model year. At the time a huge horsepower race was taking place industry wide and the 396 cu. in. Turbo-Jet was the Corvette's ticket to the party. Rated at 425 hp, it furthered the Corvettes' Bad-Boy reputation. It also represented the first time a Corvette motor was rated at over 400 hp.

A new hood was required to clear the massive motor and a handsome new "bubble hood" design (above and left) was introduced. Below: Functional vents in the side nicely broke up the area. Indications are that due to supply problems at the time, a number of small block Corvettes left the factory with the big block hood.

Most of the horsepower advantage in the new engine could be found in the design of the heads which were nicknamed "porcupine heads", a reference to the way the valves were located at odd angles similar to the quills on a porcupine. The entire big block Corvette was thus sometimes known as the "fiberglass porcupine". The physically much bigger engine required an enhanced cooling system. There was another drawback; approximately 150 lbs. of added weight, all of it on the front wheels. The weight distribution changed to 51% front / 49% rear, a handling disadvantage compared to the better balanced small block alternative.

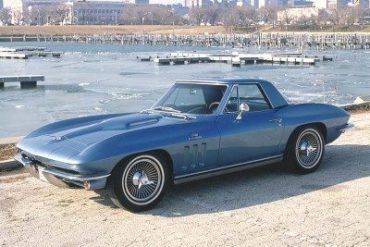

1966 Corvette

Big block engines dominated the Corvette Stingray story for 1966. They first appeared in April 1965 and as such had limited exposure. 1966 extended the big block Corvette story with the introduction of the legendary 427 cu. in. motors. They were bored and stroked versions of the 396 cu. in. 1965 big block motors and were available in two flavors: 390 hp (RPO L36, $181.20) and 425 hp (RPO L72, $312.85). The extra cost for the L72 was justified as it included four bolt mains, impact extruded aluminum pistons, a very aggressive camshaft, Holly 780 CFM carburetor mated to a aluminum intake and a free-flowing exhaust. The K66 transistorized ignition was a mandatory option with the L72. There are reports that the L72 actually featured more horsepower than the 450 hp that was quoted. The specifications were downgraded to avoid undesirable backlash from safety legislation, but enthusiasts only had to read the magazine reviews to learn what was really going on.

Drivetrain choices were nicely varied in 1966. Notice the number of axle ratios available, quite a contrast to later years when regulations would effectively limit the number of options. The "Not recommended for general driving" refers to the famous M22 "Rock Crusher" Muncie four speed transmission. The M22 was exceptionally strong but, due to its straighter cut gears, had an audible whine.

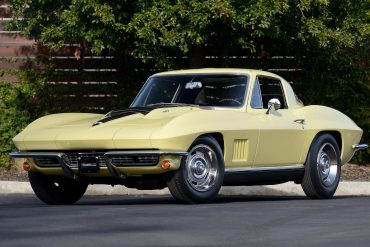

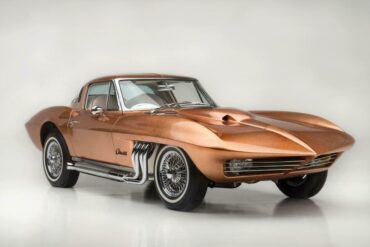

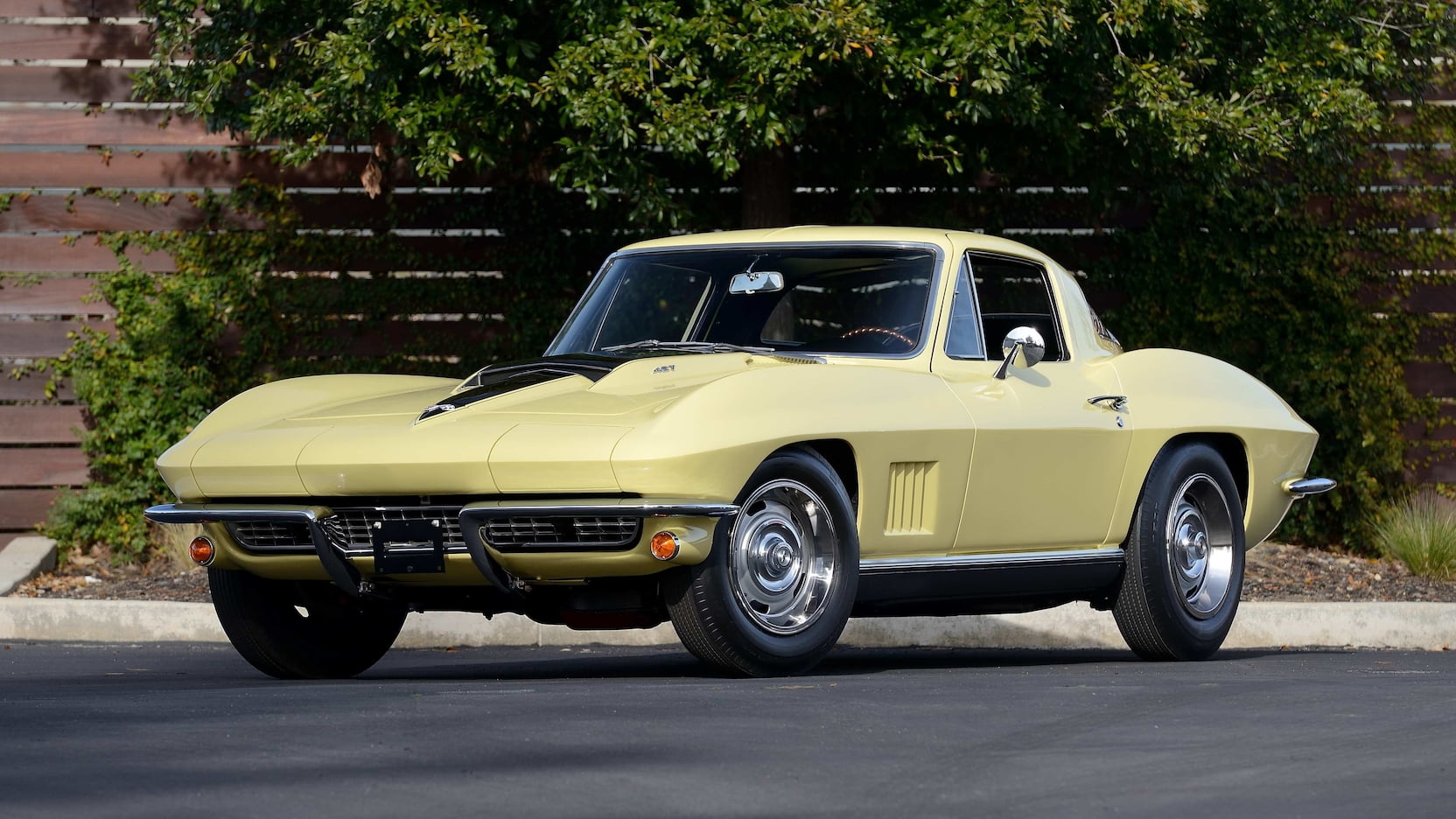

1967 Corvette

1967 Corvette1967 Corvette

1967 was the last year of the "mid year" C2 Corvette Stingrays, as the 1963 through 1967 models were known. The styling that shook the world in 1963 had proved itself everywhere, including critical praise and a sales volume that would not quit. Every model year saw a sales increase through 1966; Things cooled down for 1967 in part because it was known that a new body style would be introduced in 1968. For all cars, 1967 would be a pivotal year. Safety and smog requirements would become the law starting in 1968 and the new regulations would affect performance cars profoundly. Big blocks continued to be the way to go for Corvette purchasers in 1967; of the five engine options available, four were 427 cu. in. displacement. Multiple carburetors were the secret on the L68 (400 hp, production quantity: 2,101 (9.16%), $306) and L71 (435 hp, production quantity: 3,754 (16.36%), $437) motors. They had been used with great success in the Pontiac GTO but a GM corporate ban caused them to disappear from the Pontiac. Corvette was exempted however and three 2 bbl. Holly carburetors (below) were mounted on top of a aluminum manifold. The center carb was used in normal operation; above 2000 RPM the front and rear units kicked in. Good fuel economy was part of the bargain since only one carburetor was in use most of the time.

The C2 Corvette Market - Sales & Auctions

C2 Corvettes for Sale. This is our C2 Corvette auction and sales area. We share upcoming auctions, recent auction results, cool C2 Corvettes we find for sale and commentary on the current market for C2 Corvettes.

C2 Corvette Videos, Pictures & Wallpapers

Like the last year of the C1, the new Corvette C2 featured a long nose, a compact cabin and a short back end with peaked fenders. The general shape of the car was the same. However, there were some marked differences as well. Check out these awesome image galleries and C2 Corvette videos to enjoy the visual feast that is our favorite Corvette generation.

The C2 Corvette Newsfeed

Awesome restorations, sacrilege restomods, cool C2 Corvettes at auction or for sale, this is your newsfeed for all things C2 Corvette.

C2 Corvette Technical Research

Production and sales numbers, order guides and sales brochures, we have more C2 Corvette research than you could ever want.